On December 1, 2015, a number of important discovery-related amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure take effect. The amendments reflect an attempt to resolve conflicting authority among the Federal District Courts and clarify areas of confusion that have arisen as the bench and bar have matured in their approach to electronic discovery. The amendments are best understood as a refinement to the amendments adopted in 2006, which directly addressed the discovery of electronically stored information ("ESI") for the first time.

Although the amendments are a clear step forward in defining the obligations of courts and litigants in Federal Court, the full implication of these amendments will not be understood until courts have had opportunity to interpret and apply them. Given the contentious nature surrounding the crafting of some amendments, we can expect to see arguments by the parties (and conflicting opinions by courts) about their interpretation, particularly with respect to the amendments to Rules 26(b)(1) and 37(e).

This alert discusses the four most prominent amendments to the discovery-related Rules: 1, 26, 34, and 37. Below we list the amended rules, highlighting the updated text, followed by a brief synopsis. A comprehensive listing of the amendments to the Rules and Advisory Committee notes may be found at the Supreme Court's website.

I. Expanding the General Duties of Parties to Employ the Rules

Rule 1. Scope and Purpose

These rules govern the procedure in all civil actions and proceedings in the United States district courts, except as stated in Rule 81. They should be construed and, administered, and employed by the court and the parties to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding.

Synopsis:

Although Rule 1 has been amended to require parties, not just the district courts, to employ the Rules to "secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding," what is perhaps more important is what is not in the amended Rule 1. The Committee considered inserting "cooperation" into the rule, but decided not to do so. Instead, the Committee stated in the advisory notes that "[m]ost lawyers and parties cooperate to achieve these ends" and that "[e]ffective advocacy is consistent with – and indeed depends upon – cooperative and proportional use of procedure." While the Committee Note emphasizes that this Rule change does not create a new or independent source of sanctions, at least one judge has already pushed back on this by stating that the court has inherent authority to sanction parties for failing to cooperate.

II. Scope of Discovery and Cost Shifting

Rule 26. Duty to Disclose; General Provisions Governing Discovery

* * * * *

(b) Discovery Scope and Limits.

(1) Scope in General. Unless otherwise limited by court order, the scope of discovery is as follows: Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party's claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case, considering the importance of the issues at stake in the action, the amount in controversy, the parties' relative access to relevant information, the parties' resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit. Information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible in evidence to be discoverable. —including the existence, description, nature, custody, condition, and location of any documents or other tangible things and the identity and location of persons who know of any discoverable matter. For good cause, the court may order discovery of any matter relevant to the subject matter involved in the action. Relevant information need not be admissible at the trial if the discovery appears reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence. All discovery is subject to the limitations imposed by Rule 26(b)(2)(C).

(2) Limitations on Frequency and Extent.

* * * * *

(C) When Required. On motion or on its own, the court must limit the frequency or extent of discovery otherwise allowed by these rules or by local rule if it determines that:

* * * * *

(iii) the burden or expense of proposed discovery is outside the scope permitted by Rule 26(b)(1)outweighs its likely benefit, considering the needs of the case, the amount in controversy, the parties' resources, the importance of the issues at stake in the action, and the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues.

* * * * *

(c) Protective Orders.

(1) In General. A party or any person from whom discovery is sought may move for a protective order in the court where the action is pending — or as an alternative on matters relating to a deposition, in the court for the district where the deposition will be taken. The motion must include a certification that the movant has in good faith conferred or attempted to confer with other affected parties in an effort to resolve the dispute without court action. The court may, for good cause, issue an order to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense, including one or more of the following:

* * * * *

(B) specifying terms, including time and place or the allocation of expenses, for the disclosure or discovery;

Synopsis of Amendments to Rule 26(b)(1):

The amendments to Rule 26(b)(1) are intended to prevent parties from broadening the scope of discovery to "the subject matter of the case" upon a showing of good cause. This was the old standard that was changed in the early 1980s to "relevant to claims and defenses." but some courts had failed to recognize that the updated rule narrowed discovery and often applied the overbroad "subject matter" standard as the baseline for discovery. The amendments intentionally narrow the scope of discovery to stop courts from using this broader formulation.

The amendment makes clear that if a document is relevant and within the scope of discovery, the mere fact that it may be inadmissible does not bar its production. The Advisory Committee note to Rule 26 remarks that the "reasonably calculated" phrase in the current Rule 26(b)(1) was removed because "[t]he phrase has been used by some, incorrectly, to define the scope of discovery" and "has continued to create problems[.]"

Proportionality is a key element of discovery and limits the scope of discovery even beyond relevance. The amendment moves the mandatory proportionality factors from the current 26(b)(2)(C)(iii) and to the forefront of 26(b)(1). The Advisory Committee note to Rule 26 explains that this was done to "restore[] the proportionality factors to their original place in defining the scope of discovery. This change reinforces the Rule 26(g) obligation of the parties to consider these factors in making discovery requests, responses, or objections." Importantly, the amended Rule 26(b)(1) includes a new factor for courts to take into consideration when determining proportionality of requests, "the parties' relative access to relevant information." While this change was made to emphasize the importance of proportionality in discovery and does not change the need for considering the marginal benefit and cost of discovery, by incorporating proportionality in the definition of scope, the amendment explicitly incorporate proportionality into preservation. Documents that are not discoverable need not be preserved. Parties preserving unilaterally, however, should not be overly aggressive in relying on proportionality to not preserve documents until the case law becomes more settled.

Reflecting the Advisory Committee's commitment to the application of proportionality throughout the discovery tools, Rules 30(a)(2) and 31(a)(2) have been amended to require the Court to grant leave to conduct oral and written depositions "to the extent consistent with Rule 26(b)(1) and (2)." Rule 33(a)(1) has been amended to allow a court to grant leave to a party to serve more than 25 interrogatories "to the extent consistent with Rule 26(b)(1) and (2)." Similarly, "court must allow additional time" beyond the seven-hour time limit for oral depositions "consistent with Rule 26(b)(1) and (2)" if needed.

Synopsis of Amendments to Rule 26(c)

The amended Rule 26(c)(1)(B) provides responding parties another tool to keep discovery proportionate and reasonable: cost shifting. A party may now ask the court to include in protective orders "allocation of expenses." The amendment abrogates the minority of cases holding that courts may not shift discovery costs unless the underlying data is not reasonably accessible. This provides an opportunity for producing parties to argue that if marginal or barely proportionate discovery is going to be allowed, it should be paid for by the requesting party to ensure that they only push for discovery where they believe the value outweighs the cost. The Advisory Notes are clear, however, that this language was not meant to change the general rule that producers pay for their discovery productions.

III. Changing How Parties Respond to Discovery Requests

Rule 34. Producing Documents, Electronically Stored Information, and Tangible Things, or Entering onto Land, for Inspection and Other Purposes

* * * * *

(b) Procedure.

* * * * *

(2) Responses and Objections.

(A) Time to Respond. The party to whom the request is directed must respond in writing within 30 days after being served or — if the request was delivered under Rule 26(d)(2) — within 30 days after the parties' first Rule 26(f) conference. A shorter or longer time may be stipulated to under Rule 29 or be ordered by the court.

(B) Responding to Each Item. For each item or category, the response must either state that inspection and related activities will be permitted as requested or state an objection with specificity the grounds for objecting to the request, including the reasons. The responding party may state that it will produce copies of documents or of electronically stored information instead of permitting inspection. The production must then be completed no later than the time for inspection specified in the request or another reasonable time specified in the response.

(C) Objections. An objection must state whether any responsive materials are being withheld on the basis of that objection. An objection to part of a request must specify the part and permit inspection of the rest.

Synopsis:

Quickening the Ability to Serve Document Requests

The amendments to Rule 34 may significantly change how parties respond to discovery requests and produce documents. First, the amended Rule 34(b)(2)(A) works in tandem with the amended Rule 26(d)(2), which now permits service of discovery requests before a Rule 26(f) conference in certain cases and considers such early requests "to have been served at the first Rule 26(f) conference" regardless of when the request was sent or delivered. The purpose of these two rules is to encourage requesting parties to serve their requests before 26(f) conferences so that the parties can better meet and confer about the scope of the discovery. However, one of the other practical effects of this rule is that parties may respond to discovery very quickly, potentially even before the Rule 16 scheduling conference.

Specificity and Choice to Produce

The first amendments two amendments to Rule 34(b)(2)(B) simply memorialize the existing law in most federal courts. Requiring a party to state "with specificity the grounds for objecting" to a request tracks Rule 33(b)(4)'s current requirement that parties must state objections to interrogatories with specificity and many courts had incorporated it into Rule 34. See, e.g., Mancia v. Mayflower Textile Servs. Co., 253 F.R.D. 354, 359-60 (D. Md. 2008). Second, the amended Rule 34(b)(2)(B) allows a party to specify whether it will allow inspection of ESI or produce copies of ESI. While it is helpful to have this explicitly states in the Rules, most courts had found that a party can choose to produce or permit an inspection and that a court could not force an inspection over objection without good cause. See, e.g., In re Ford Motor Co., 345 F.3d 1315, 1316-17 (11th Cir. 2003).

Informing Requesting Party When Productions will be Complete

The amendment to Rule 34(b)(2)(B), however, may have the biggest impact on the behavior of responding parties and require them to state the reasonable period of time in which it will complete its production. At the time a party responds to requests it may be hard to know when productions will be substantially complete. For example, the scope of discovery is likely still being negotiated and a party may still be investigating the volume of information that may be at issue. Moreover, while the Advisory Committee understood that productions are often made on a "rolling" basis, the Advisory Committee notes counsel that "[w]hen it is necessary to make the production in stages the response should specify the beginning and end dates of the production." In light of this amendment and the accompanying note, therefore, counsel should be careful not to rely on open-ended promises to produce information on a rolling basis. In addition, it is unclear what obligation a party has to supplement this date or what will happen to a party who fails to complete its productions by the date it estimates in its response.

Are Objections Causing the Responding Party to Withhold Documents?

Finally, the biggest philosophical change to Rule 34 is included in Rule 34(b)(2)(C), which will now state: "An objection must state whether any responsive materials are being withheld on the basis of that objection." The Advisory Committee comments that this amendment is intended to "end the confusion that frequently arises when a producing party states several objections and still produces information, leaving the requesting party uncertain whether any relevant and responsive information has been withheld on the basis of the objections." The Advisory Committee notes also make an effort to allay concerns that the amendment will place a significant burden on objecting parties to "show their work":

The producing party does not need to provide a detailed description or log of all documents withheld, but does need to alert other parties to the fact that documents have been withheld and thereby facilitate an informed discussion of the objection. An objection that states the limits that have controlled the search for responsive and relevant materials qualifies as a statement that the materials have been "withheld."

Thus, to comply with this obligation, a responding party could disclose the filters it used to search for responsive information, such as date restrictions, lists of specific data sources, or search terms. This is not without risk as it could generate more scrutiny and motion practice as requesting parties ask to broaden responding parties' searches. In fact, the Rules do not require these specific types of disclosure and parties often wish to avoid such disclosures for the purposes of protecting confidential or privileged information. In such cases, parties should attempt to fashion alternative means of satisfying the amended Rule, such as describing specifically what you are looking for (not "how"), which should provide requesting parties enough information to object if they think the search is too narrow. Until the courts have had time to determine the practical implementation of Rule 34(b)(2)(C), the extent to which litigants will be required to disclose their search and review criteria will remain unclear.

IV. Setting Clear Standards for Spoliation of ESI

Rule 37. Failure to Make Disclosures or to Cooperate in Discovery; Sanctions

* * * * *

(e) Failure to Provide Preserve Electronically Stored Information. Absent exceptional circumstances, a court may not impose sanctions under these rules on a party for failing to provide electronically stored information lost as a result of the routine, good-faith operation of an electronic information system. If electronically stored information that should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation is lost because a party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and it cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery, the court:

(1) upon finding prejudice to another party from loss of the information, may order measures no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice; or

(2) only upon finding that the party acted with the intent to deprive another party of the information's use in the litigation may:

(A) presume that the lost information was unfavorable to the party;

(B) instruct the jury that it may or must presume the information was unfavorable to the party; or

(C) dismiss the action or enter a default judgment.

Synopsis:

Perhaps the most contentiously disputed amendment, Rule 37(e) has been amended to create a consistent standard for spoliation in all Federal courts. Prior to the amendment, the standards of culpability ranged from mere negligence to recklessness and willful conduct among the various Circuit Courts. As stated in the Advisory Notes, the new Rule specifically overrules Second Circuit precedent (Residential Funding Corp. v. DeGeorge Fin. Corp., 306 F.3d 99 (2d Cir. 2002)) that arguably authorized adverse-inference instructions on a finding of negligence or gross negligence.

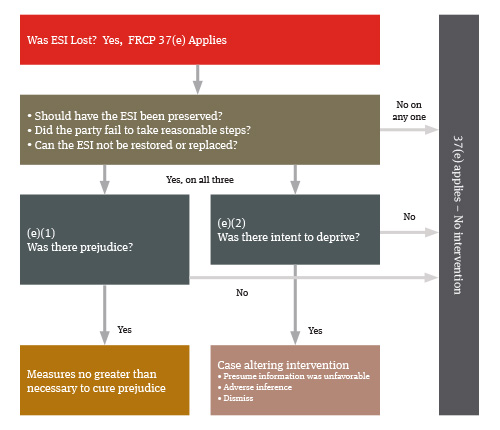

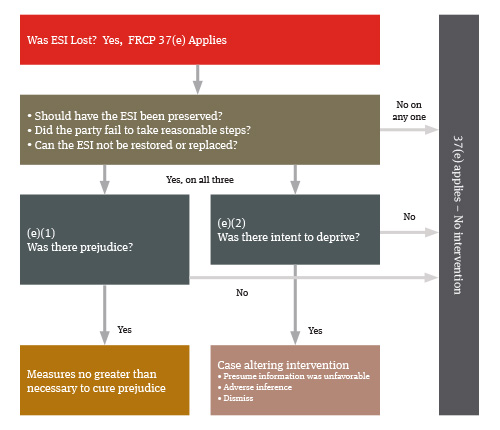

Now, Rule 37 provides a tiered approach to loss of ESI. First, intervention by the Court under Rule 37(e) is not permitted unless three elements are established: (1) ESI that should have been preserved has been lost, and (2) the party losing the ESI failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and (3) the lost ESI cannot be restored or replaced. If these three elements are established, then the court may either: (1) order curative measures if the requesting party is prejudiced by the loss of ESI; or (2) levy the enumerated sanctions if the court determines that the responding party acted with intent to deprive the requesting party of the ESI.

Curative measures can be broad and could include precluding a party from presenting evidence, deeming some facts as having been established, or permitting the parties to present evidence and argument to the jury regarding the loss of information. On the other hand, case altering intervention, including adverse inferences, are only available where a requesting party has lost or destroyed the data with an intent to deprive the requesting party of its use in the litigation (which arguably requires the loss to occur in the current matter and not in a former one). Moreover, the Advisory Notes caution courts about these severe sanctions and emphasize the least draconian sanction should be levied:

Courts should exercise caution, however, in using the measures specified in (e)(2). Finding an intent to deprive another party of the lost information's use in the litigation does not require a court to adopt any of the measures listed in subdivision (e)(2). The remedy should fit the wrong, and the severe measures authorized by this subdivision should not be used when the information lost was relatively unimportant or lesser measures such as those specified in subdivision (e)(1) would be sufficient to redress the loss.

Thus, while proportionality and prejudice are not explicitly within Rule 37(e)(2), the Advisory Notes make it clear that it is best read with both of these principles in mind. To make new Rule 37(e) more manageable, we have attached a flow chart to help explain the analysis.