Cartels have been described as “theft by well-dressed thieves”.1 This reference perhaps brings to mind images of police raids, individuals being escorted away in handcuffs and judges handing down jail time. Indeed, if cartels are clearly so harmful – and perpetrated by “thieves” – we would expect the punishment should fit the crime.

Looking at cartel enforcement, we have observed two trends across our global practice in recent years: first, the level of fines imposed on companies has increased continuously; second, more and more jurisdictions are criminalising cartel behaviour by individuals. This has implications not only for individuals – who face a real threat of incarceration and personal fines – but also for companies, both in terms of their options for responding to investigations and in ensuring their compliance policies are fit for purpose. In this article we focus on the second trend and show not only that the criminal cartel offence can now be found in all corners of the world, but also that prosecutors and competition authorities are increasingly prioritising enforcement against individuals responsible for cartel conduct.

The gradual criminalisation of cartel behaviour

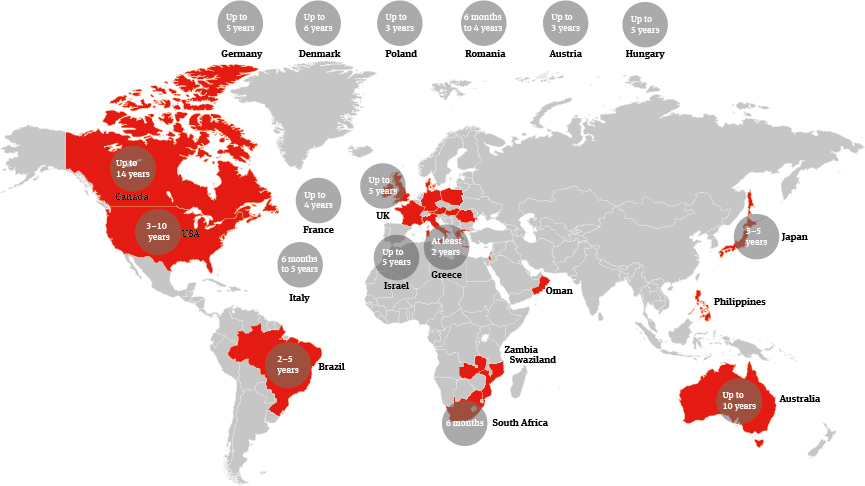

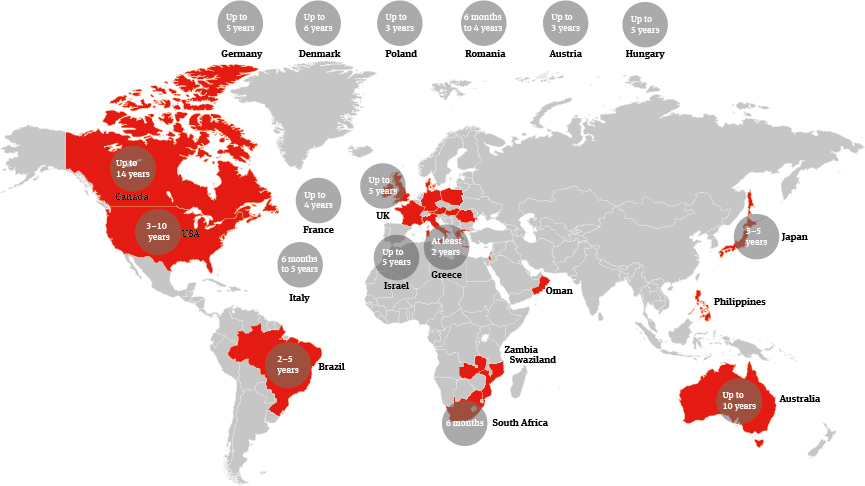

The modern proliferation of criminal cartel sanctions can be traced all the way back to the enactment of the Sherman Act in 1890 in the US. This made cartel activity a misdemeanour under section 1 (the prohibition against collusive conduct) punishable by up to a year in prison. Congress upgraded cartel activity to a felony2 in 1974 and increased the maximum prison sentence from one to three years. In 2004, the Antitrust Criminal Penalty Enhancement and Reform Act increased the maximum individual fine from US$350,000 to US$1 million and the maximum term of imprisonment from three to ten years.3

In Canada, criminal antitrust law has existed even longer than in the US, since 1889. And on paper, Canada imposes the most severe cartel sanctions for individuals in the world. In 2010, the maximum penalties were increased so that conspiracy (i.e. engaging in fixing prices, allocating customers or markets, or restricting output) is now punishable by a fine of up to CA$25 million, and/or imprisonment for a term of up to 14 years.4 Penalties for bid-rigging in Canada include a fine at the discretion of the court and/or a prison sentence of up to 14 years.5

Outside of North America, cartel enforcement has generally been of an administrative and civil character – targeting the company alone. Criminal sanctions have crept into the antitrust enforcement regimes in other jurisdictions only gradually, in the last decade or two. In the UK, a criminal cartel offence became effective in 2003, which provided that where an individual had acted dishonestly by entering into or implementing a prohibited cartel agreement (direct or indirect price-fixing, limiting or preventing production or supply, sharing customers or markets or bid rigging), a prison sentence of up to five years could be imposed.6 In Brazil, price-fixing has been prosecutable as a criminal offence since the 1990’s.7 Individual cartel offenders may be sentenced to prison for two to five years.

Denmark is the most recent European country to introduce a criminal cartel offence. Since 2013, engaging in a cartel is a personal criminal offence punishable by imprisonment if the individual’s participation in a cartel was deliberate and of a grievous nature based on its scale and adverse effects. The maximum sentence is 18 months;8 but this can extend to up to six years where there are aggravating circumstances.9

A number of other EU Member States have criminalised cartel conduct to a lesser extent. In France, Greece and Romania, it is possible for cartel behaviour to be prosecuted under fraud offence provisions.10 In Germany, Austria, Italy, Poland and Hungary criminal sanctions only apply to bid-rigging.11 Close to Europe, Israel criminalised cartel conduct in 1988 under the Restrictive Trade Practices of Law 1988. A maximum prison sentence of three years applies (or five years if there are aggravating circumstances).

Criminal sanctions are also found in the Asia-Pacific region. For example, in Japan criminal penalties apply under the Antimonopoly Law, including a term of imprisonment for individuals. The maximum term of imprisonment was increased in 2009 from three to five years. In Korea, the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act was revised in 2013 to facilitate increased referrals for prosecutions of individuals by public prosecutors, where individuals are potentially liable for a fine and/or prison sentence of up to three years. Separate offences relating to bid rigging also apply under the criminal codes in Japan, for public employees, and more generally in Korea.12 Australia introduced a cartel offence in 2009.13 The maximum criminal sanction for individuals is a prison sentence of ten years and/or a fine of AU$340,000. New Zealand has recently considered following suit, but draft legislation has been shelved for the time being.14 South Africa is the latest country to introduce personal criminal liability for cartel conduct.15 Certain sections of the legislation came into effect from 1 May 2016, seven and a half years after being approved by Parliament. Under the new laws individuals who caused their company to participate in cartel conduct or “knowingly acquiesced” to that effect are criminally liable for a maximum fine of R2000 (approximately £86) and/or imprisonment, currently up to six months.16

There is also a list of countries where cartels have been criminalised from the more recent introduction of specific antitrust regimes along with civil penalties, for example the Philippines (2015), Oman (2014), Zambia (2010) and Swaziland (2008). There are a number of other countries where amendments to the competition law are currently pending which will introduce criminal sanctions.

Paper tigers and setbacks

Despite the gradual proliferation of the criminal cartel offence around the world, the reality is that custodial sentences have been imposed only rarely outside the US. Even in the US itself prison sentences only became a regular occurrence in the early 1970s. In many respects, this reflected judicial and public attitudes: courts (and juries) have been reluctant to penalise individuals for a crime that ultimately benefits the company and shareholders. They are more willing to impose hefty fines on the company. Authorities in many jurisdictions have been hesitant to bring criminal charges because of concern that a jury will not view individual cartel conduct as sufficiently reprehensible to warrant the stigma of a conviction – and this will be a more obvious concern where competition law is a recent phenomenon.

A lack of prosecutions or established civil competition enforcement tradition also inevitably means the authorities in some countries lack experience and to some extent still face hurdles (for example, in their institutional design or because of potential adverse implications of a leniency programme). Setbacks in prosecuting individual cartel offenders in recent years clearly have not helped. A prominent example is the prosecution in the UK in the BA/Virgin fuel surcharge case, where the prosecution against four BA executives collapsed spectacularly due to evidence management problems. The Office of Fair Trading (now the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA)) and the Serious Fraud Office – which were responsible for cartel investigations – argued that the reason for the lack of successful prosecutions was due to the difficulty faced in convincing a jury that an individual had acted “dishonestly”, which was one of the requirements for proving the criminal cartel offence in the UK prior to its amendment in 2013.17

In Canada, since at least 1996 no cartel offender has spent any time in prison.18 Several executives have been sentenced to prison but their sentences were commuted to community service or home detention. In 2015, a number of individuals charged with 60 counts of bid-rigging for federal government contracts were found not guilty or acquitted.19 The track records in Brazil and Japan do not fare much better; in both countries prison sentences imposed against cartel offenders have either been suspended or overturned on appeal (for example, the Brazilian air cargo cartel decision of 2014 and the Japanese bearing manufacturers cartel decision of 2015).

As of today, actual imprisonment outside the US has only been imposed in the UK and Israel. In Israel, most custodial sentences imposed were suspended and the few actual prison sentences have not exceeded nine months.20 In the UK, the only successful criminal prosecution that resulted in prison sentences was in the Marine Hose case.21 However, the circumstances in that prosecution were unusual given that the individuals involved in the cartel pleaded guilty to the offence as part of a plea bargaining arrangement already agreed in the US.

Renewed focus on individuals: cartel offence 2.0

Despite the patchy record of imprisonment, authorities are demonstrating an increased determination to send cartel offenders to prison.

The UK is a good example. The Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 amended the offence to remove the dishonesty test for conduct that takes place on or after 1 April 2014. On paper, this should make it easier for the CMA to prove its case against individuals. In this respect it is important to note that the acquittals in the Galvanised Steel Tanks case in 201522 – the CMA’s most recent prosecution – involved an offence that occurred before 1 April 2014 and therefore was still subject to the old test. It is likely that the CMA will fare better in prosecutions based on the new test but in the meantime the CMA continues to seek prosecution of individuals under the old dishonesty standard.

Recently Canada has also taken steps to strengthen its enforcement.23 The Safe Streets and Communities Act 2012 restricted the availability of conditional sentences (i.e. preferring community service sentences for individuals) for all offences for which the maximum term of imprisonment is 14 years or life and for specified offences, prosecuted by way of indictment, for which the maximum term of imprisonment is ten years. As a result, jail time for competition law infringements is inevitable.

Similar steps have been taken in Australia, where the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has recently created a serious cartel conduct unit which works closely with the Director of Public Prosecutions in circumstances where criminal action may be appropriate.24 In February this year both the Canadian and Australian competition authorities announced that they expect criminal cartel prosecutions to be initiated later in 2016.25

In the US there has been a steady rise in the average prison sentence for defendants prosecuted under Federal antitrust law, which has increased from eight months in the 1990’s to 24 months for fiscal years 2010 to 2015. However, the most notable recent trend has been the substantial increase in fines. Criminal fines and monetary penalties in 2015 almost tripled compared to the previous fiscal year's record high of US$1.3 billion.26 Nonetheless, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has refuted criticism that it is merely “drunk on fines” and affirmed its longstanding belief that individual criminal liability is the most potent deterrent.27 In September 2015, Deputy Attorney General Sally Q. Yates issued a memorandum (now known as the “Yates Memo”),28 which is intended to provide policy guidance on DOJ prosecutions. The Yates Memo among other things sets out that the DOJ’s investigation should concentrate on individual offenders from the very beginning. The anticipated effect of this new approach is that individuals will be under increased pressure to apply for leniency to reveal on-going anti-competitive conduct and more leniency applications. The DOJ has also warned that more extraditions of foreign national defendants would follow in the near future, after successfully completing extraditions of two individuals for antitrust crimes in 2014.29

In Australia, the ACCC now looks to identify individuals at an early stage in investigations for referral to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions for possible prosecution before the Federal Court and has a number of such cases in the pipe line.30

Conclusion

The designation of cartel conduct as a criminal offence is now reflected in statute books in every region of the world. This proliferation will only increase. Of course, the effectiveness of criminal sanctions as a deterrent to breaches of antitrust rules depends on the frequency and effectiveness of enforcement just as much as – if not more than – the existence of the offence on the statute books in the first place. For authorities this is a learning process or, perhaps as in the case of the UK, a process of trial and error. But the evolution of criminal enforcement in other countries will certainly not take as long as in the US. At the same time, recent developments in enforcement policy in the US and the UK show that individuals can expect to face prosecution in those jurisdictions as the rule rather than the exception.

The message for individuals and companies as their employers is clear:

- Where a personal criminal offence applies, the relevant authority is likely to investigate and prioritise a prosecution of individuals responsible for anti-competitive conduct in parallel with the civil procedure against the company – companies need to anticipate how they would respond to an investigation where individuals are also prosecuted.

- Internal procedures need to anticipate the risk that individuals may look to avail themselves of whistleblowing opportunities to secure immunity from prosecution under leniency programmes without prior knowledge of the company.

- Companies may need to review their antitrust compliance policies and training programmes to ensure that they cover individual sanctions that may apply in all of the jurisdictions in which the business operates and to ensure that employees and directors are fully appraised of their responsibilities and the sanctions that can apply to them personally.