The guide

Nicola Liu lays out the map of her life | Issue 21 | 2022

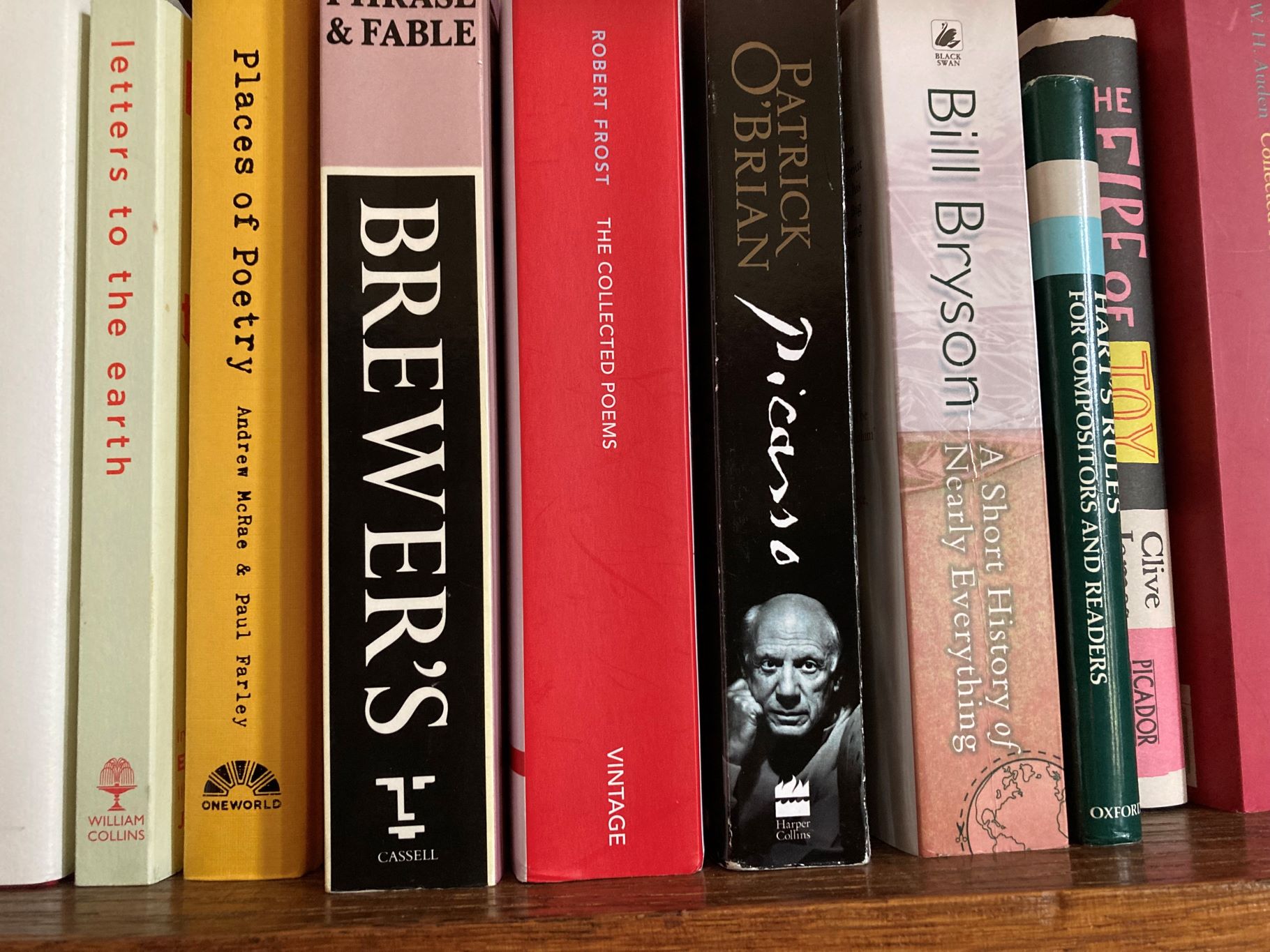

Patrick Bracher in Johannesburg on a life littered with books

My love of slow reading is good for my happiness and bad for my garden. Given the choice between a book and a trowel in my hand, there is no contest.

The first book I bought from my meagre earnings as an 18-year-old articled clerk was Pears’ Cyclopaedia. It was of no particular use to me to know whether the archbishop or the prime minister should sit on the right of the queen at a banquet, but I have spent a lifetime chasing down new facts, useful and useless. I will read a toothpaste tube if nothing else is around.

The South African apartheid government labelled everyone who opposed their inhuman principles as communists, which turned those who did to socialist reading. The highlight was Isaac Deutscher’s trilogy on The Prophet Armed, Unarmed, and Outcast, about the fascinating fanatic Leon Trotsky. Somehow that reading led to the challenging depths of existentialism. Dostoevsky, of course, but Jean-Paul Sartre was my particular hero for being an active and involved factory-gates philosopher, who was never better analysed than by Iris Murdoch in Sarte: Romantic Rationalist.

Philosophy is a lifetime journey. That journey has brought me recently to John Gray including the disturbing charm of Feline Philosophy. We give meaning to life by the art of diversion and books are my very meaningful diversion. None better than Bertrand Russell‘s eloquent, elegant and entertaining History of Western Philosophy.

I own more dictionaries, grammar books and usage books than most libraries. I have a passion for good language. Not for grammar, which is mostly misguided, as Henry Hitchings’ The Language Wars will tell you. I mean the use of ordinary words that please, inspire and persuade. I delight in the many expressive ways that the English language is used worldwide. Research in dictionaries for the right word (which I do frequently) gives the added joy of serendipitous findings that online research cannot match. The most charming language book I have is The Elements of Eloquence by Mark Forsyth.

Reading popular science makes some sense of everything. Anything by Richard Feynman proves why his biography is called Genius. An easy start is a Short History of Nearly Everything by the smooth-penned Bill Bryson. David Bodanis’s e=mc2 could not do a better job of turning science into a storybook. I am no closer to understanding quantum mechanics—yet I am comforted by Feynman’s much-repeated statement: “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.”

My learning about the planet and nature began with Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which was published in 1962 and is still in print and once again on my bedside table. This was one of the first environmental science books to sway public opinion and get the indiscriminate use of DDT banned—which helped the insect population, whose important role is amusingly and compellingly described in the recent Extraordinary Insects: The Fabulous, Indispensable Creatures Who Run Our World by Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson.

It’s not all facts for me. I have shelves-full of oft-read poetry books, including Robert Frost’s Collected Works, Robert Graves and Thomas Hardy with their incomparable meter and clear meaning; Derek Walcott, whose Omeros is one of the great epic poems; the poetic insights of Maya Angelou; and hundreds of other journeys into poetic language as a refuge. I returned in the week of writing this essay to Robert Burns, who reminds us in For a’ That and a’ That that a person of independent mind looks and laughs at the trappings of power. Burns knew full well that there are not ‘diverse’ people, just people.

My pursuit of human rights has led me through hours of book-learned insights. My journey began in my early twenties with Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, still one of the best books on gender equality. I am reading Non-binary Lives. These shared stories of the challenges of non-binary people illustrate why gender neutral attitudes and gender neutral legal drafting are no longer a choice. Prejudice and logic are opposites. That truth leaps out of The Matter of Black Lives: Writing from the New Yorker, an anthology of writings on black lives in the United States, starting with James Baldwin.

I possess three books with perfect conclusions. The role of philosophy is summarised in the last paragraph of Bertrand Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy. Tom Holland ends his exploration of the rise of the great Middle East religions, In the Shadow of the Sword, with the message that the word triumphs over the sword. And Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow concludes with the lesson that power is no longer ‘having access to data’. Power is knowing what to ignore.

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025