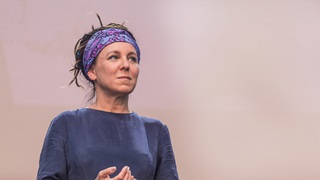

Olga

Izabela Duda on Olga Tokarczuk | Issue 16 | 2019

The violets are children with bare feet

The leaves are fresh on the almond trees,

spring water rains from stone walls;

trotting lightly, the donkeys choose

the friendlier of the river’s banks;

the girls with the darkest eyes

clamber on the squeaking cart, aloof.

March is a baby, laughing already, in its swaddling clothes.

And you can forget the winter,

who, bent by bundles of wood,

have told your beads,

mile after freezing mile,

to roast your face by the fire.

Now ticks come back to the horses,

in the stables flies stir the air,

and children with bare feet

charge upon clumps of violet.

Translation by Allen Prowle

In Matera, in the south of Italy, is an oil painting by Carlo Levi depicting the region of Lucania, and its poverty. The figure of the poet Rocco Scotellaro dominates the canvas. Behind him are the calanchi – clay hills eroded by wind and rain, hardened by the sun. He is in the piazza, talking, trying perhaps to shift people out of their apathy.

Scotellaro was determined to eradicate ignorance, superstition and fatalism, and to change the lives of Italians in the south: he used his poetry as one means to do this. Through his choice of imagery, messages and vocabulary, he acknowledged the dignity of a peasant’s life.

In this poem, ‘Le viole sono dei fanciulli scalzi’, he takes spring as a metaphor. After the rain, the first buds appear and life begins. We are aware that not everything (of the winter) has passed, because memory serves to make each of us feel its weight; but there is the hope of rebirth, emphasising the poet’s dream of a place where youngsters, though barefoot like the violets, are filled with vitality. The difficulties of real life are not overcome: they are carried along, mixed with hope, and trust.

Today, the landscape of Lucania has new contours: land reform has done away with the grand estates, but, apart from Metapontino, the land is not cultivated. A region once dominated by a rural peasant landscape is punctuated by oil drills, wind turbines and a scattering of tourist villages on the coast. Everywhere, there are signs of the emigration of skilled individuals. Among the locals, the suspicion and apathy that existed so many years ago still prevail.

In 1946, at just twenty-three, Scotellaro became mayor of Tricarico (in Basilicata). His role in the workers’ struggles and the campaign for land reform led to his imprisonment on false charges, and to his early death.

Perhaps we need a ‘new’ Rocco Scotellaro?

Rocco Scotellaro is the poet-mayor of his home town Tricarico. In his poetry he ‘sings’ about his poor – sometimes very poor – land and its inhabitants. The world he described still exists, largely unchanged.

‘Le viole sono dei fanciulli scalzi’ is a tribute to the land that is reawakening: the almond trees flower and the water, already warm, flows in shallow streams. The girls forget the long winter passed sitting by the hearth. With the heat, the ticks on the skins of the farm animals will return and mosquitoes will fill the stalls, but the youngsters are happy: they kick off their wooden shoes and, barefoot, they collect violets to give to their loved ones.

Scotellaro is the poet of his memory; but he also writes as an intellectual about clarity and disillusionment. The reality he inhabits is that of post-1945 southern Italy. His works shun the elegiac themes of much of the literature of the time. For him, there are no rules, no parameters. His is a poetry focused on struggle (lotta).

His personal history, his experience of political struggle, his contact with the key protagonists of social transformation, his incarceration – these are all themes present in his work. His death from a heart attack at the age of thirty also casts a shadow over his work.

To reconstruct the person, you need to know something of his relations with the artist Carlo Levi, the academic Manlio Rossi-Doria, the publishing house Laterza, the journalist Vittore Fiore and the powerful Olivetti company. But his work speaks for him. Rocco Scotellaro remained fiercely connected to his land, its people, and to his identity – as a poet–artist: and an intellectual.

A former professor of Italian literature, Annarosa Brandi comes from the Basilicata region in Italy, where Rocco Scotellaro lived. Mariolina Paparella is active in literary initiatives in the south of Italy and was a professor of German. ‘The violets are children with bare feet’ is reproduced here by kind permission of Allen Prowle. Prowle’s translations of poems by Rocco Scotellaro can be found in Your Call keeps Us Awake, published by Smokestack Books in 2013.

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025