Publication

Navigating international trade and tariffs

Recent tariffs and other trade measures have transformed the international trade landscape, impacting almost every sector, region and business worldwide.

Publication | November 2017

The Commercial Court and Chancery Division of the High Court in London have hosted large-scale financial litigation for many years. New cases in these Courts may presage important international trends in regulation or liability and the outcomes of conflict can inform risk allocation in the financial sector.

In this article, we examine trends in recent and ongoing financial litigation in these Courts, give specific guidance on how likely different types of dispute are to settle and identify the surprisingly sudden emergence of a new source of liability for banks based on fraud. The information in this article comes from Norton Rose Fulbright’s award-winning Court Intelligence Database (“CID”, see Box).

Systematic monitoring of cases traditionally focuses on judgments: the outcomes of cases that are fought all the way to a decisive result. But this gives no information on the first and most vital questions for any litigant: whether the case will go to trial and how long it will take. CID monitors ongoing litigation and so can answer these questions. Interestingly, the most important factor is whether the case is principally about mis-selling. Mis-selling cases are more likely to be settled before going to trial.

Overall, just under 25 per cent of CID cases proceed to trial and judgment. This is actually fairly high compared to litigation generally. CID cases may represent larger disputes where there has been extensive discussion prior to the commencement of legal proceedings, so that those that end in litigation are relatively intractable. Clearly, whether a dispute is settled depends on the particular circumstances of that claim. Nevertheless, the starting point for risk evaluation and management by a bank receiving a claim form is that just over three-quarters of claims will not reach final judgment.

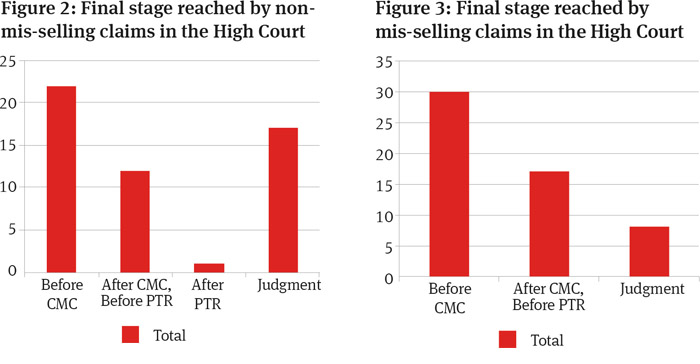

For a mis-selling case, the chance of settlement is higher. Only about 15 per cent of mis-selling claims are taken all the way to judgment. For non-mis-selling claims, the ratio is proportionately higher: about one-third of all non-mis-selling claims go to trial. The claimants in mis-selling claims tend to be less sophisticated and the amounts at stake smaller. Conversely, many non-mis-selling claims are large disputes where the issuance of a claim form follows extensive negotiation, so that a higher proportion of non-misselling claims may settle before a claim form is issued.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the final stage that mis-selling and non-misselling claims reach. Apart from the overall rate of settlement, these two Figures also reveal further patterns. Mis-selling claims appear to have a fairly constant probability of settling over time – claims are dealt with at a steady rate resulting in fewer surviving to the later stages. Non-mis-selling claims do not exhibit a constant probability of settling. Instead, they appear to be marked by specific milestones which may precipitate settlement. In particular, they tend to settle soon after issuance or close to trial – perhaps marked by exchange of expert witness evidence or disclosure.

This pattern accords with a litigator’s intuition as to the progress of large cases. Issuance of a claim may concentrate the parties’ attention and lead to settlement. If it does not, then expert evidence and disclosure generally mark a further step change in the level of knowledge of the parties. If the case does not settle quickly, then the parties may decide to undertake disclosure and obtain expert evidence so that they will have a clearer idea as to the strength of the case. This precipitates a further wave of settlement later in the life of the litigation.

The pattern in Figure 3 is likely to emerge when legal costs are small in relation to the size of the claim: there is less opportunity cost in obtaining expert evidence, for instance, to evaluate more precisely the strength of the case. Where legal costs are higher in proportion to the size of the claim, they are a constant drain and so there is a continuing incentive to settle, leading to the pattern of Figure 2. Alternative fee arrangements may also be a greater factor in these claims.

Intuition may be useful; sometimes it may mislead. The importance of the conclusions set out here is that they are based on objective data. Figures 2 and 3 show real differences in the course of litigation. Banks and financial institutions should take account of this when planning the size and distribution of their legal spending and their approach to determining claims.

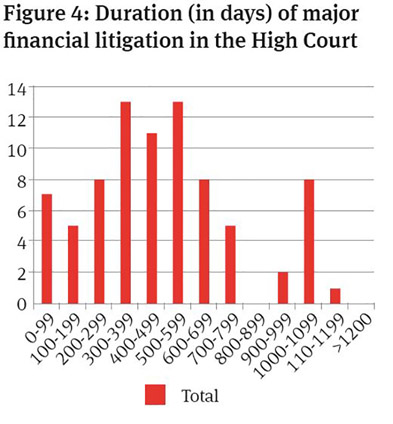

This is yet another basic question for litigants where traditionally the answer has been supplied by intuition without any attempt at verification or is limited only to the experience of one law firm. Using CID, Figure 4 shows the overall duration of major financial litigation in the High Court, from cases that settle immediately after issuance of proceedings through to those that are taken to final judgment.

We can also separate out the duration of cases by their outcome: cases that go all the way to judgment last longer than those that settle. The overall average for litigation is just over 500 days – a little less than a year and a half. The average for cases that go all the way to judgment is just under 700 days – nearly two years.

Again, this is crucial information for litigants, especially when taking into account the data on the likelihood of settlement. This data is inevitably backward-looking to some degree: we only know how long a case lasts once it has finished. Nevertheless, it is based on cases currently settling or otherwise being determined and so is as up-todate as possible.

We have excluded from this calculation cases that end without any clear marker: those that are simply allowed to fade away when no further action is taken but without any notice on the court record that fixes the date of settlement or discontinuance. This is because the precise date the case ends is not known. Including these cases would push the overall average for litigation up to nearly 600 days. This probably corresponds to the delay in knowing that a case in this category has actually ended, so that it does not affect the conclusions set out here.

The English courts have traditionally played their part in the role of London as a global financial centre, providing a home for large-scale international disputes. Following the vote for Brexit, there has been increased speculation as to whether the scale and volume of litigation in the English courts would be affected, particularly in relation to banking and financial services.

Of course, Brexit can only be one factor in the overall volume of litigation. Fallout from the financial crisis, the state of the economy and the impact of regulation will all impact the scale and nature of important banking and finance cases litigated in the English courts. Nevertheless, this is still an important benchmark for the financial services industry in the UK.

In fact, over the last few years, the number of important banking and finance cases has remained relatively stable, within a range of approximately 80 to 100 cases. Given the average duration of eighteen months set out above, it follows that about 50 to 60 cases per year are resolved and are replaced by new cases.

Two points follow from the broadly static general trend. Firstly, the end of financial crisis-related disputes has had surprisingly little effect on the volume of these cases. Cases stemming from the events of 2007 – 2009 and subject to the standard six year limitation period would cause a bulge in litigation ending in around 2017. But other sources of litigation appear to have filled the gap – we consider the breakdown of cases by category further below.

Secondly, there has not yet been any significant effect from Brexit. The total number of cases arguably shows a gentle decline within the overall range – continued monitoring will be able to show whether this decline becomes established. It may be that Brexit effects are yet to be felt. The European system for judicial co-operation and enforcement is still in place and will not change before 2019 – any effect would be purely a result of psychology rather than substance. Efforts by the UK Government to propose continued judicial co-operation and by English lawyers to explain that Brexit will have minimal consequences for the conduct of English litigation appear to have been effective so far.

New arguments appear for the first time in pleadings. If a financial institution only consults judgments in decided cases, it will not see over three-quarters of these arguments at all and the remainder only after about two years. By then, any litigation trend would be well-established. Accordingly, it is vital for risk management and strategic planning to be able to spot new arguments at the pleading stage.

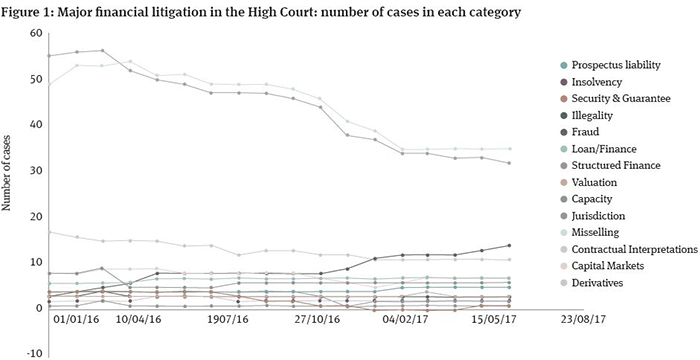

Using CID, Figure 1 sets out how many cases fall within a number of different categories, looking at major financial litigation in the High Court. Two trends appear. Firstly, there has been a marked decline in litigation relating to mis-selling and derivatives (and these two categories largely overlap).

This is undoubtedly due to time elapsed since the financial crisis. Abrupt dislocations in interest rates and other financial metrics during 2007 – 2009 led to litigation which, taking into account the six year limitation period and two year average case duration, is now winding down. This is a gradual process and new sources of mis-selling claims continue to arise, also generally related to market dislocations since the financial crisis. Nevertheless, it appears that the peak in derivatives mis-selling cases has passed – at least those based on interest rate hedging products sold to SMEs.

As set out above, the overall volume of cases has not seen a marked decline – so what is replacing derivatives mis-selling claims? All other categories of claim show little change, apart from one: fraud. There has been a steep increase in claims that involve allegations of fraud. A few years ago, there were typically two or three such cases involving banks being litigated at any one time. By the middle of 2017, there were 14 cases involving fraud. The lesson for banks and financial institutions is clear: they should be prepared to manage a greater number of fraud cases and they should understand the risk factors that lead to disputes involving fraud.

The factual matrix underlying each particular dispute determines whether allegations of fraud are made and whether they are successful. However, it is possible to extract from recent and current cases various factors that might motivate allegations of fraud:

Circumventing basis clauses“Basis clauses” are statements in a contract that set out the basis on which the parties are dealing, eg, a statement that a counterparty is a sophisticated investor. Courts have strictly enforced basis clauses, even where they effectively constitute exclusions of liability. They are not subject to the reasonableness limitations that apply to exclusion clauses as set out in the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (UCTA). In fact, there have even been examples where the Court has held that a basis clause successfully precluded liability even where that clause would have been deemed unreasonable if UCTA had applied – see our previous articles on basis clauses, Contractual estoppel in mis-selling claims and Contractual estoppel and the duty to advise: Where are we now?.

An allegation of fraud is one way to revive a claim that is otherwise precluded by a basis clause. A party cannot rely on a basis clause to negate liability based on fraud. Accordingly, strict enforcement of basis clauses by the Courts over the last few years has created pressure which may have been relieved by increased pleading of fraud.

This suggests that fraud allegations arise where there has been a breakdown in the relationship between an investor and a financial institution and where the relationship between them was mediated by a contract that included a basis clause. This would include mis-selling claims as well as claims more widely involving bankclient relationships.

Obtaining new remediesEnglish courts have traditionally provided a wide range of remedies for fraud. In recent years, this has been further enhanced by their zeal to combat money laundering, bribery and corruption. Worldwide freezing orders, constructive trusts, equitable tracing and equitable receivership all form part of the flexible and effective tools available particularly in cases of fraud.

But the key remedial advantage when pleading fraud is the availability of rescission: the right to cancel the contract and put the parties in the position they were in before the contract was entered into. Where one party is seeking to extricate itself from a bad bargain, this is a tempting prospect.

Claims to rescind interest rate derivatives based on manipulation of LIBOR are an example. Interest rates moved unexpectedly following the financial crisis, leaving a number of businesses with hedging arrangements that were expensive and worthless. Basing a claim that would otherwise be simple mis-selling on fraudulent misrepresentation allows a party to cancel an unprofitable contract where no damages would be recoverable.

This suggests that fraud claims arise when banks or their counterparties are trapped in bad contracts, perhaps following abrupt market dislocations. For instance, they could be consumers alleging interest rate hedging products were mis-sold, or they could be securitisation issuers seeking to unwind one leg of back-to-back currency hedging arrangements. In all these cases, rescission is a powerful remedy, if fraud can be established.

Increased regulatory oversightSince the financial crisis, banks have seen increased regulation and regulators have pursued wrongdoing with greater zeal. There have been several wide-ranging reviews of behaviour during and since the financial crisis, putting into the public domain voluminous detail relating to bank activity regarding LIBOR and other indices, interest rate hedges and many other products. Claimants may attempt to piggy-back on regulatory findings where they are investors in products that have been investigated by regulators or that refer directly or indirectly to indices that have been investigated by regulators. These claims are generally phrased in terms of fraud allegations.

Longer limitation periodsClaims involving fraud may be able to take advantage of longer limitation periods – in particular, where the claimant is not aware of the facts underlying the fraud until after the transaction is entered into. Given that the financial crisis occurred in 2008 – 2009 and that the standard limitation period is six years, many disputes are now in the critical stage immediately following expiry of the limitation period, when all claims other than based on fraud are barred.

This suggests that some of the fraud allegations may be motivated by an attempt to circumvent limitation periods and that this will naturally decline as we move beyond the critical period for most claims.

Will the trend continue?Our analysis is inherently forwardlooking because we are examining current and ongoing litigation rather than decisions from completed cases. So the trends we identify here will start to be reflected in judgments in the next few years. In short, more judgments dealing with fraud will be a feature of English jurisprudence irrespective of whether the trend identified by CID continues.

Nevertheless, it is interesting to speculate as to whether new disputes will continue to allege fraud and whether the total volume of disputes before English courts will remain steady. Most of the drivers for fraud allegations listed above are still active. The political and business environment appears to have permanently embedded an increased focus on regulation and wrongdoing, so regulatory oversight and enhanced fraud remedies will continue to underpin fraud claims. Until the expansive view of basis clauses is changed – and many academic commentators think it should be changed – then this factor will also persist.

The only factor with waning influence is the extended limitation periods available for some fraud claims. Overall, then, fraud is likely to continue growing in importance. There may even be a positive feedback effect: when judgments featuring fraud arguments increase in frequency, this could inspire new claimants to include fraud arguments. In this way, a new higher level of fraud claims may become a visible feature of the litigation system.

The Court Intelligence Database analysis of current litigation gives valuable insight to financial participants in English litigation. Definitive, objective data is available on what kinds of cases settle, how long litigation takes and what sort of arguments feature in current cases.

English litigation has proven itself resilient to the gradual decline of financial crisis disputes, partly due to the new trend of increasing fraud claims. The great imponderable, of course, is how Brexit will affect the level and nature of litigation in the English courts. This will be addressed in further updates from the Court Intelligence Database in coming editions of the BFDR.

| Norton Rose Fulbright’s Court Intelligence Database

The Norton Rose Fulbright Court Intelligence Database (CID) is a “big data” cloud-based database which monitors all live cases involving banks and financial institutions in the English courts. This is in addition to the small proportion that end in decided judgments after several years. The claims can be broken down by subject matter, law firm, barrister, the stage of the claim, the identity of the parties involved, and their status in the litigation. CID not only assists in spotting litigation trends but it also checks and tracks the types of arguments employed by parties and counsel, the progress of a case, and where parties are taking inconsistent positions in different disputes. The Court Intelligence Database won the “Knowledge Management Innovation’ award at the 2016 Legal Week Innovation Awards and was also shortlisted in the “Innovation in Business Development and Knowledge Sharing” category at the FT Innovative Lawyer Europe Awards 2016. |

Publication

Recent tariffs and other trade measures have transformed the international trade landscape, impacting almost every sector, region and business worldwide.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025