Mark Strand

The poet

RE | Issue 12 | 2017

…I lie sleeping with one eye open,

Hoping

That nothing, nothing will happen.

Alexandra Howe on Mark Strand (1934—2014)

“I think the reality of [a] poem is a very ghostly one”, Mark Strand—Pulitzer Prize-winning author and former United States poet laureate—said in an interview for The Paris Review in 1998. “It suggests, it suggests, it suggests again.”

To understand the truth of that, consider the title poem in his first collection, Sleeping With One Eye Open (published in 1964). The speaker lies in bed ‘saddled with spooks’, watching the ‘fishy light’ of the moon slide across the floor and ‘Hoping | That nothing, nothing will happen.’ There is something childlike, and universal, in that feeling of mid-night dread; for who has not, at some time in her life, lain uneasily awake in the witching hour, troubled by unspecific horrors.

Many years later, Strand told the radio program Weekend America that he could no longer remember what he was thinking of when he wrote the poem in 1962. It spoke, he said “to a certain anxiety I experienced back in the early ‘60s. I was afraid the United States would go to war…I think it’s a poem surrounded by a great deal of silence.” It is in this silence, this ‘beyondness’, that the reality of the poem resides, as elusive and as powerful as the night terrors it describes.

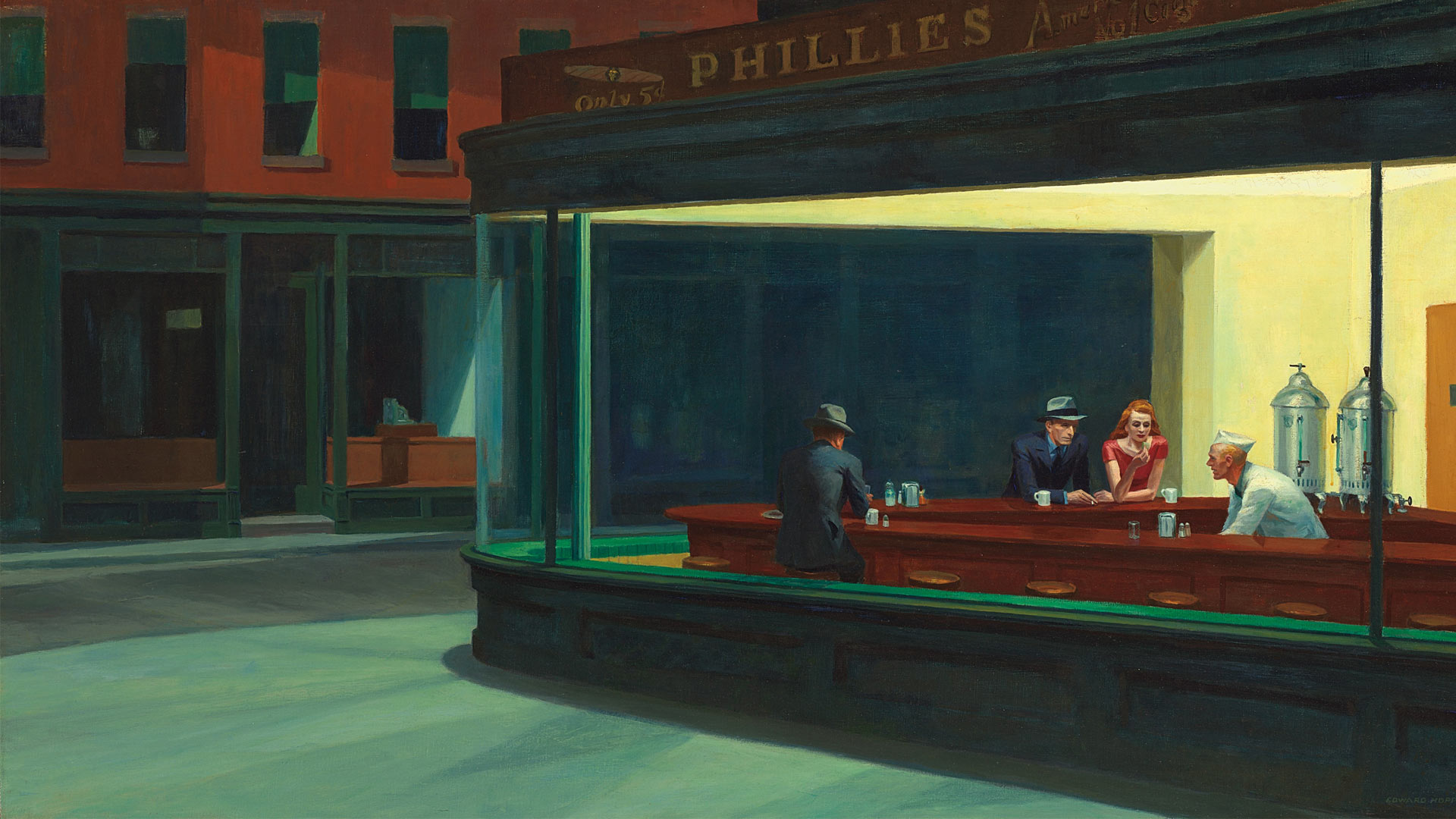

The effect of Strand’s poetry is similar to that of the paintings of Edward Hopper. Strand originally planned to become a visual artist and published several volumes of art criticism. “So much of what occurs within a Hopper”, he wrote in 1994, “seems related to something in the invisible realm beyond its borders.” In the painting Nighthawks, three customers and a waiter in a harshly lit all-night diner are viewed from the dark street outside. Strand points out that the trapezoid sides of the diner window through which we look slant off to a vanishing point beyond the canvas, propelling us past the tableau which momentarily absorbs us: “[w]e are not drawn into the diner but are led alongside it”. The scene suggests narrative possibilities which carry the viewer beyond what she sees.

Strand liked to be mystified: “it’s really that place which is unreachable, or mysterious, at which [a] poem becomes ours, finally, becomes the possession of the reader.” Meaning, then, is personal, and mutable, and not enforced by the poet.

With thanks to Elsa Stern, for introducing me to Mark Strand.

First published in RE: issue 12 (2017)

Alexandra Howe (New York) is the arts editor of RE.