To date, multilateral and development finance institutions have taken a significant role in catalysing climate finance. Aggregate finance levels reached US$62 billion in 2014, an increase from US$52 billion in 20133. This estimate used the definition of public finance and private finance directly associated with public finance interventions and therefore did not account for private finance indirectly mobilised by capacity building, policy-related interventions and the role of broader enabling environments.

Whilst it is expected that a significant proportion of the US$100 billion target associated with the Paris Agreement will be met by public finance, it is critical that private finance is also mobilised to meet the scale of investment required to achieve climate change goals. Public finance alone, often constrained by budgetary restrictions, will not be sufficient.

In the first week of 2016 Marrakech climate negotiations, 38 developed nations and the European Commission published a roadmap to build confidence and increase transparency and predictability about how the US$100 billion target will be achieved. The roadmap provided projections on where developed countries planned to be by 2020, including US$67 billion a year of public finance and US$24 billion from private finance.

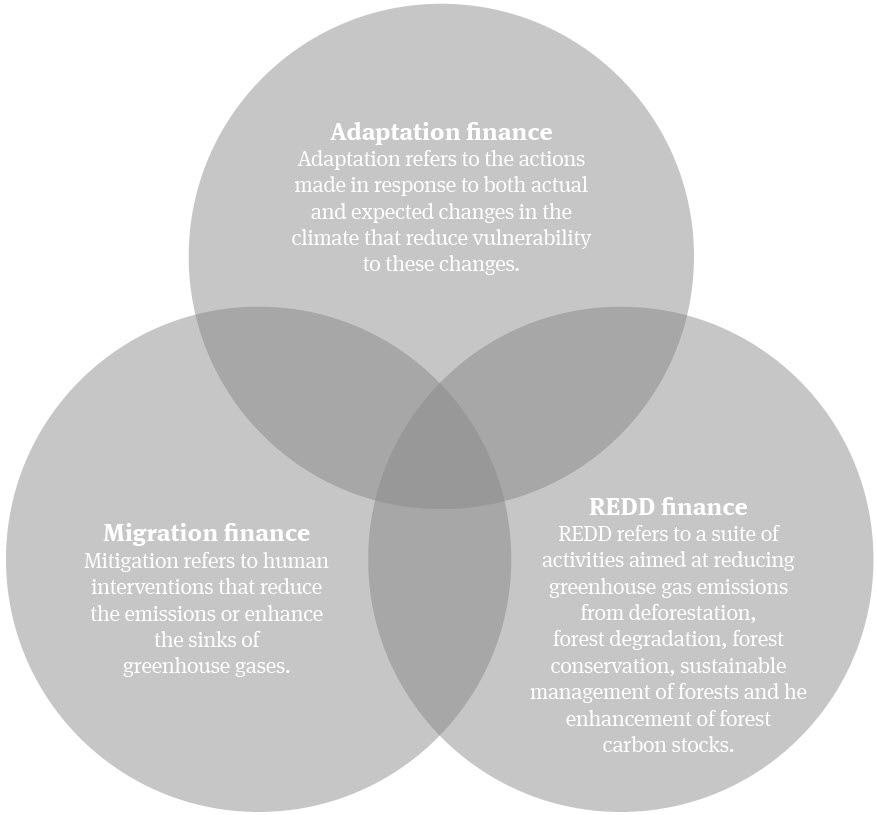

The issue of climate finance is gaining momentum during 2017. The Prime Minister of Fiji announced that adaptation finance would be a key issue for their incoming Presidency of COP 23, which will take place in Bonn in November 2017. Germany, which holds the Presidency of the G20 for 2017, has announced that its priorities include green financing and climate and energy policies. . The delegates of the recent Bonn Climate Change Conference also reaffirmed the importance of climate finance.

One example of an active mobilisation of funds so far this year is the investment in April 2017 by the Green Climate Fund of USD$250 million in equity to the European Investment Bank for GEEREF NeXt – a ‘fund of funds’. The fund aims to attract additional private sector investment of USD$500 million over the next 15 years. It is intended that the funds will be used to finance over 200 renewable energy and energy efficiency projects in eligible developing countries across the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and the Pacific. The programme aims to support the commercial environment for renewable and efficiency projects in the beneficiary states by absorbing risk in an anchor investor role or via equity commitments designed to stimulate additional capital for projects. GEEREF NeXt will either directly invest into beneficiary projects or operate indirectly through specialised funds.