Publication

Navigating international trade and tariffs

Impacts of evolving trade regulations and compliance risks

United Kingdom | Publication | June 2025

In insurance law, a warranty is effectively a promise that something will or will not be done or that a certain state of affairs exists or will exist. Prior to the 2015 Act, insurance warranties under non-consumer insurance contracts were required to be complied with exactly, regardless of whether they were material to the underlying risk or not. A breach of warranty, even if remedied prior to the occurrence of any loss, would discharge the insurer from all liability under the policy. This position was outlined in the predecessor to the 2015 Act, the Marine Insurance Act 1906 (the 1906 Act).

One of the key features of the 1906 Act was that it permitted the inclusion of ‘basis of contract’ clauses, providing that an insurance contract has been entered into on the basis of all the information provided by the insured. Such clauses had the effect of converting all pre-contractual information supplied to insurers into warranties which, if breached under the 1906 Act, would automatically render the cover void.

As noted by the Court of Appeal in Lonham v Scotbeef, the old common law approach, codified in the 1906 Act, had developed during a period where the insured would have been far more informed about the underlying risk than the insurer. As the market developed through the century that followed, this consideration became less relevant and it was therefore important to draw a clear distinction between representations and warranties and provide greater protection for policyholders through a more nuanced set of remedies. Notably, section 9(2) of the 2015 Act prohibits the operation of ‘basis of contract’ clauses by providing that a representation is not capable of being converted into a warranty by any means.

Scotbeef Limited (Scotbeef) is a producer and distributor of meat for retail purposes which had entered into a contract with D&S Storage Limited (DS) for the freezing and storage of its meat products at DS’ warehouse facilities. In October 2019, six pallets of meat were found to have been contaminated with mould to the extent that they were no longer fit for human or animal consumption. In July 2020, Scotbeef issued a claim for damages against DS.

In its defence, DS claimed that its contract with Scotbeef had been entered into on the standard terms and conditions of a trade association that DS was a member of (the FSDF Conditions). The FSDF Conditions contained certain limitations on liability and a time bar on claims that would have been favourable to DS’ case. Prior to the Court of Appeal hearing however, there had already been a finding of fact by the High Court that the FSDF Conditions had not been incorporated into the contract between the two parties.

In November 2021, DS was wound up after having gone into liquidation. Lonham Group Limited (Lonham), DS’ insurer at the relevant time, was subsequently joined to the action pursuant to the Third Parties (Rights against Insurers) Act 2010. The point at issue was therefore whether DS had the benefit of valid insurance coverage under its policy with Lonham that could indemnify its liability to Scotbeef.

The most relevant clause in the policy was as follows:

“Duty of Assured Clause:

“It is a condition precedent to the liability of Underwriters hereunder:-

(hereinafter, the Clause).

Importantly, the policy also provided that a breach of a condition precedent would entitle Lonham to avoid the whole claim.

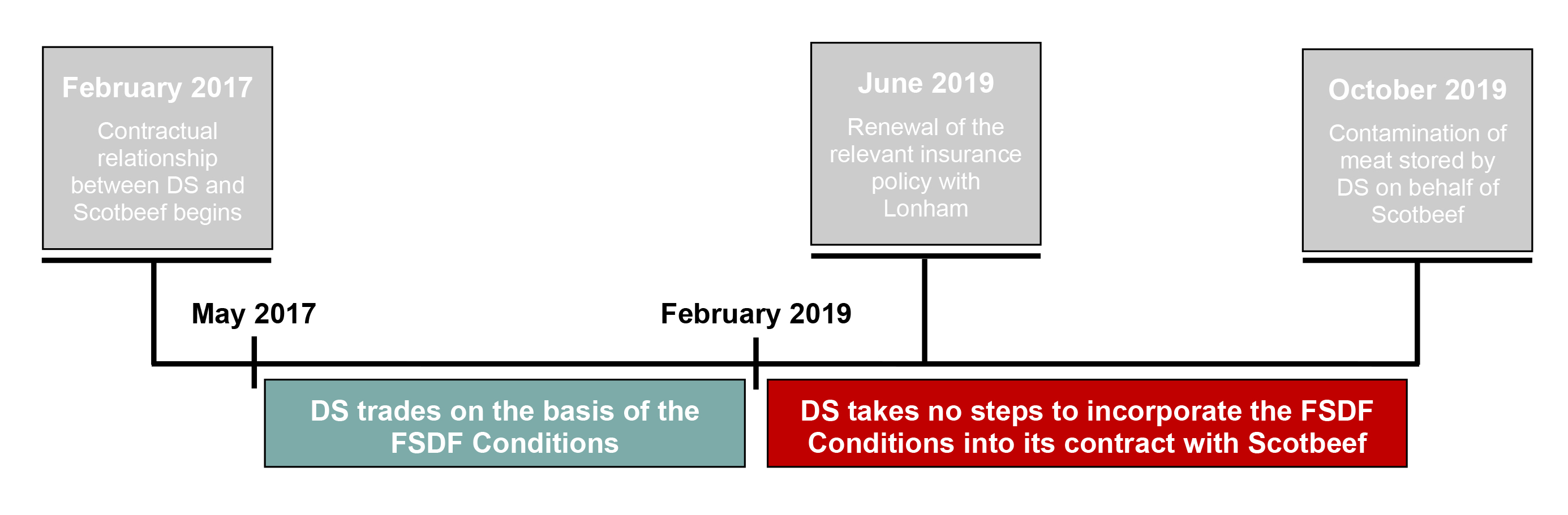

The specific chronology of events is illustrated in the below timeline.

Scotbeef’s principal argument was that the Clause, in its entirety, was a representation and therefore could not be converted into a warranty pursuant to section 9(2) of the 2015 Act. Additionally, Scotbeef argued that none of the limbs under the Clause could be conditions precedent as the effect of a breach would be more disadvantageous to DS than the remedies available for misrepresentation and DS and Lonham had not agreed to contract out of the 2015 Act. The key question was therefore whether the three limbs of the Clause were representations or warranties.

The High Court and the Court of Appeal agreed that the first limb was a pre-contractual representation given that (i) it was a statement which related to existing trade arrangements with existing customers at the point at which the policy incepted and (ii) this is clearly information upon which Lonham would have assessed the underlying risk and made its underwriting decision.

The High Court also found however, that all three limbs ought to be read together and that all three should therefore be considered representations. As all three limbs were deemed to be representations, they could not stand as conditions precedent and any breach would be governed by section 3 of the 2015 Act and the duty of fair presentation.

Overturning the High Court’s decision and finding in favour of Lonham, Fraser LJ delivered the unanimous judgment of the Court of Appeal and noted that the three limbs sought to deal with each possible permutation of DS’ dealings with its customers, namely:

(a) existing arrangements with existing customers prior to the inception of the policy;

(b) existing arrangements with existing customers which continue after the inception of the

policy;

(c) new arrangements with existing customers entered into after the inception of the policy; and

(d) new arrangements with new customers entered into after the inception of policy.

The Court of Appeal therefore concluded that the first limb of the Clause addressed permutation (a) whereas the second and third limbs addressed permutations (b) to (d). As such, it was found that the second and third limbs sought to regulate the conduct of the insured during the policy term and therefore fell squarely within the standard meaning of a warranty in an insurance context; they were promises by the insured that certain requirements would be satisfied after the contract had been made.

As the second and third limbs of the Clause were found to be warranties, section 9(2) of the 2015 Act was not relevant and the limbs were not restricted from being conditions precedent.

At the point at which the policy incepted, DS was not trading with Scotbeef pursuant to the FSDF Conditions that had been disclosed to Lonham. DS was therefore in breach of the second limb of the Clause and, as the policy expressly stated that the insurer would be entitled to avoid the whole claim in the event of a breach of a condition precedent, Lonham was not liable to indemnify Scotbeef.

Due to the contrasting remedies available for a breach of warranty under the 2015 Act in comparison to a breach of the duty of fair presentation, the Court of Appeal’s categorisation of the second limb of the Clause as a warranty is what proved crucial for Lonham’s case.

Breach of the duty of fair presentation

Scotbeef sought to argue that each limb under the Clause was a representation because, on the basis of a breach of the duty of fair presentation alone, Lonham would not have been able to avoid DS’ claim. The 2015 Act provides that insurers may avoid an insurance contract following a breach of the duty of fair presentation only if (i) the breach was deliberate or reckless or (ii) the insurer would not have entered into the contract on any terms in the absence of the breach.

DS’ breach was innocent and there was no suggestion that Lonham would have completely refused to insure DS had it been aware of the actual terms on which DS was trading. As such, the policy would have been deemed to continue on amended terms, most likely in respect of the premium charged, and Lonham would have been liable to indemnify Scotbeef.

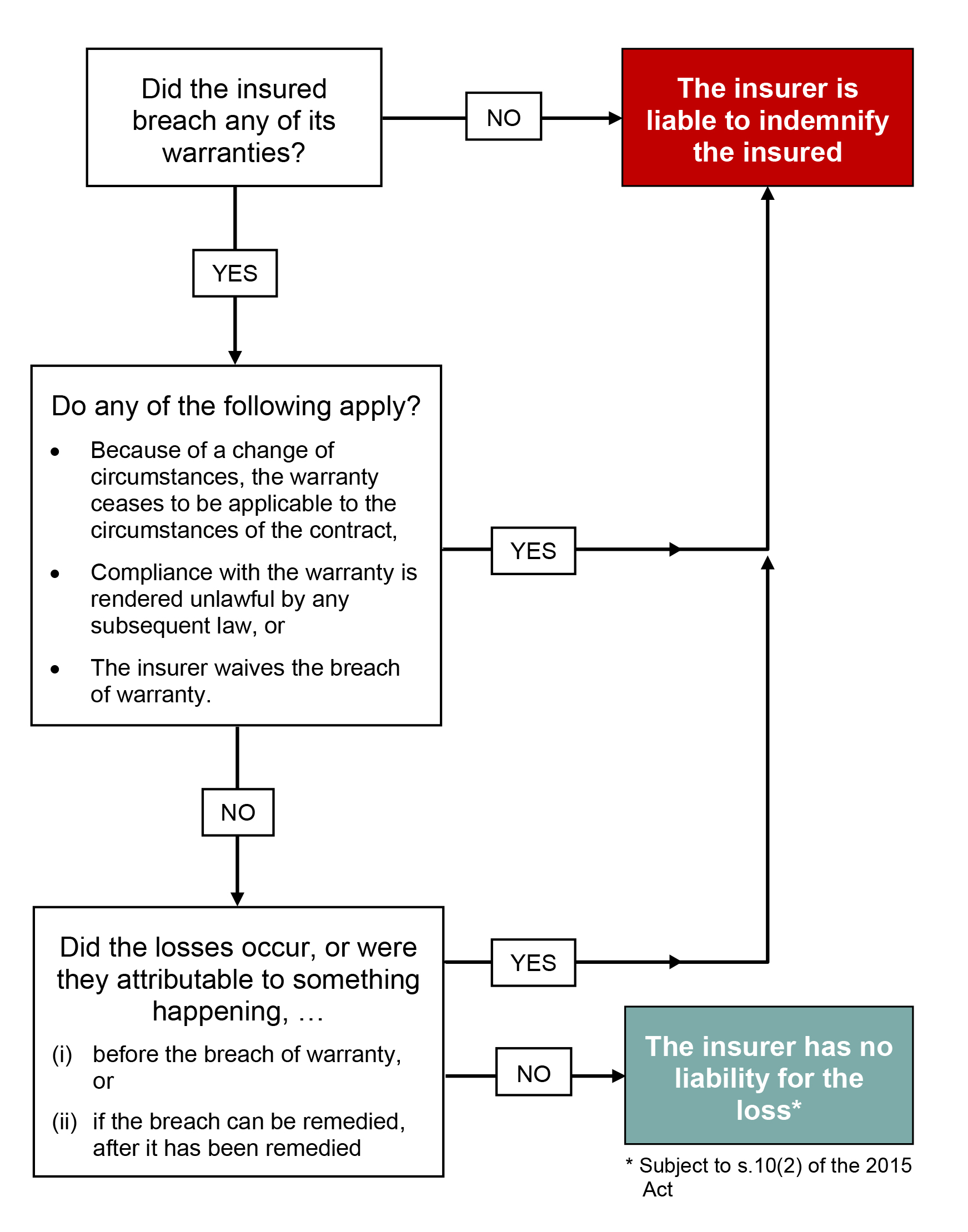

The different remedies available to an insurer after a breach of the duty of fair presentation are illustrated in the below decision tree.

Breach of warranty

By contrast, the only available remedy for a breach of warranty under the 2015 Act is the discharge of the insurer’s liability in respect of any loss occurring, or attributable to something happening, after such warranty has been breached but before the breach has been remedied.

Section 10(3) of the 2015 Act also provides that this remedy does not apply if:

On the facts of Lonham v Scotbeef, none of the mitigating factors in section 10(3) were applicable and therefore Lonham was entitled to avoid the claim.

The Court of Appeal’s judgment serves as an important reminder of the restrictions imposed by the 2015 Act on certain classes of terms. Due to the operation of section 9(2) of the 2015 Act, the first limb of the Clause could not serve as a condition precedent to liability (granting a right to avoid any claim following a breach of the duty of fair presentation). A potential alternative, therefore, would be to contract out of the 2015 Act (albeit only to the extent that this represents a commercially viable solution).

In this case, DS was also in breach of the second limb of the Clause. While the Court of Appeal found that this limb operated as a warranty, the significance of ensuring that all warranties are specifically designated in policy wordings should not be underestimated.

Publication

Impacts of evolving trade regulations and compliance risks

Publication

Low carbon projects, especially those involving hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCS), play a crucial role in the journey towards global decarbonization.

Publication

As a general remark, Indonesia has not, at the date of preparing this summary, issued any regulation on hydrogen production, distribution and trade. It is expected that the upcoming New and Renewable Energy Law will provide a legal framework for the exploitation and utilisation of various new energy sources, including hydrogen.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025