Publication

Navigating international trade and tariffs

Impacts of evolving trade regulations and compliance risks

Australia | Publication | July 2025

This publication is Norton Rose Fulbright’s second monthly update ahead of Australia’s first offshore wind auction. In this month’s update, we provide our views on:

You can find our previous instalment here.

As the market matures and more projects are sited in close proximity to one another, we have observed an increase in “wind theft” or “wake effect” related disputes between European offshore wind projects in recent years.

“Wake effect” describes the potential impact on wind speeds and air turbulence caused by one offshore wind project on another adjacent project, which could have the effect of reducing the output of the downwind turbines. While the legal “right to wind” is tenuous, there is a possibility that an afflicted project could sue for damages. This could potentially give rise to an unknown quantum of liability for the other project, which is of concern to both sponsors and lenders alike should such a claim succeed. Regardless of the legal position, there is also the economic risk of reduced output by the affected project; which if left uncompensated, could affect the quantum of revenue generated by the project. This in turn could hamper its ability to meet its equity return targets, repay lenders and meet its financial coverage ratios.

The best way to address “wake effect” or wake loss risk is to appropriately space developments so that there is no or minimal wake from nearby turbines. Where this is not possible, power adjustments and wake loss compensation agreements are being contemplated. Under the latter, we would typically expect an independent expert to ascertain the level of compensation payable, and the parties agree that this represents the full and sole remedy of the afflicted party against its neighbouring project. To the extent that the risk of wake effect compensation will ultimately reside with the shareholders, it would be usual for the sponsor to bear their proportion of the aggregate amount of compensation claimed by the neighbouring project. We have deep experience structuring many of these arrangements in other markets.

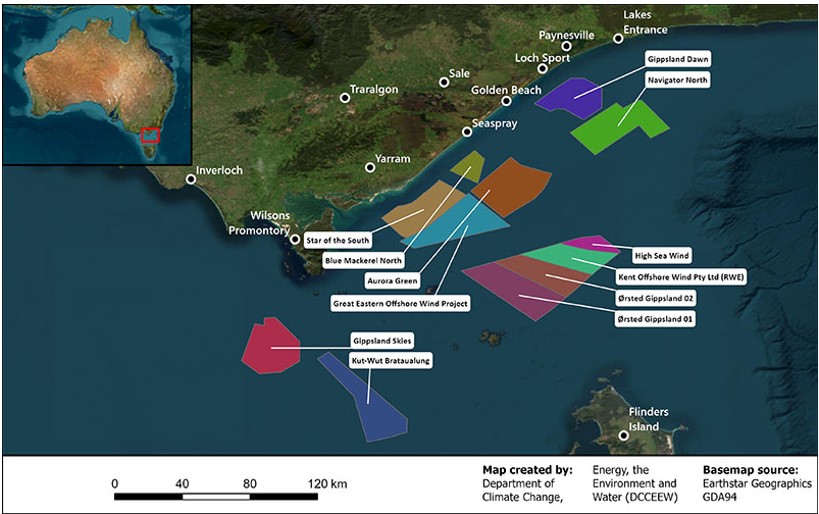

The extent to which wake loss has been taken into account when awarding feasibility licenses in Gippsland remains unclear. However, given all Gippsland projects were awarded feasibility licenses at about the same time, proponents are aware of the potential locations of other nearby offshore wind farms at the time of conducting their feasibility studies. This contrasts with some of the scenarios in Europe where new offshore wind farms have been consented and built after others were already operating. Accordingly, this may reduce litigation risk in Gippsland at least insofar as the current round of projects in development are concerned. The disputes in Europe are also partly caused by uncertainty over the precise impact of the wake effect. As offshore wind farms are built in clusters (as will be the case in Gippsland), it will be important to assess and quantify any wake effect or wake loss. To this end, proponents should wake effect and wake losses should be appropriately modelled and any associated risks allocated so that it does not become an unforeseen issue once the projects become operational.

A new referral has been lodged under the Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) for the development of Victoria’s Renewable Energy Terminal at the Port of Hastings.

The new referral, which was open for public comment until 9 July 2025, comes after the first referral (which was lodged in 2023) was rejected by the Federal Minister for Environment. Initially, the proposed development was adjudged to have ‘clearly unacceptable’ impacts on the internationally protected Western Port Ramsar Wetlands.

The Port of Hastings is the Victorian Government’s preferred port for turbine assembly for the state’s pipeline of offshore wind projects, in part because it is the closest deep-water port to the Gippsland declared area.

Following the initial rejection, the Victorian Minister for Planning required an environmental effects statement be prepared, identifying alternative project layouts and designs to avoid and mitigate environmental impacts, particularly those which were previously deemed clearly unacceptable.

Under the new referral, the design footprint has been modified to provide for a 70 per cent reduction in dredging volume and a 35 per cent reduction in reclamation areas compared to the previous referral. Additionally, the reclamation areas have been repositioned to minimise impacts to the Western Port Ramsar Wetlands.

In the last few years, First Nations underwater cultural heritage (UCH) has become an increasing topic of discussion, due to several factors including a focus on offshore projects, rising Indigenous advocacy and growing public awareness, and shifts in policy and archaeology.

In 2024, the Department of Climate Change, Energy and Water released the ‘Guidelines - Assessing and Managing Impacts to Underwater Cultural Heritage in Australian Waters’ to provide guidance to proponents on the requirements of the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Cth) (UCH Act) and set the minimum standard for UCH management in near and offshore development in Australian waters.

The UCH Act defines “underwater cultural heritage” to mean ‘any trace of human existence that has a cultural, historical or archaeological character and is located under water’. As such, the definition captures tangible First Nations cultural heritage evidencing previous inhabitation of now underwater areas. The UCH Act principally operates as follows:

Although the Guidelines developed under the UCH Act are not legally binding, they provide useful direction for proponents and archaeologists undertaking underwater activities on how to identify and protect First Nations UCH. The Guidelines recommend risk management strategies to avoid non-compliance with the UCH Act and outline a risk mitigation process that should be undertaken before commencing work. This includes early engagement with relevant First Nations groups, undertaking of cultural heritage impact assessments and considering the broader cultural landscape, not just physical artefacts.

With thanks to Jack Brown for his contribution.

Publication

Impacts of evolving trade regulations and compliance risks

Publication

Low carbon projects, especially those involving hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCS), play a crucial role in the journey towards global decarbonization.

Publication

As a general remark, Indonesia has not, at the date of preparing this summary, issued any regulation on hydrogen production, distribution and trade. It is expected that the upcoming New and Renewable Energy Law will provide a legal framework for the exploitation and utilisation of various new energy sources, including hydrogen.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025