Charlotte Mew

Alexandra Howe reads 'I So Liked Spring' by Charlotte Mew | Issue 19 | 2021

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

from Musée des Beaux Arts

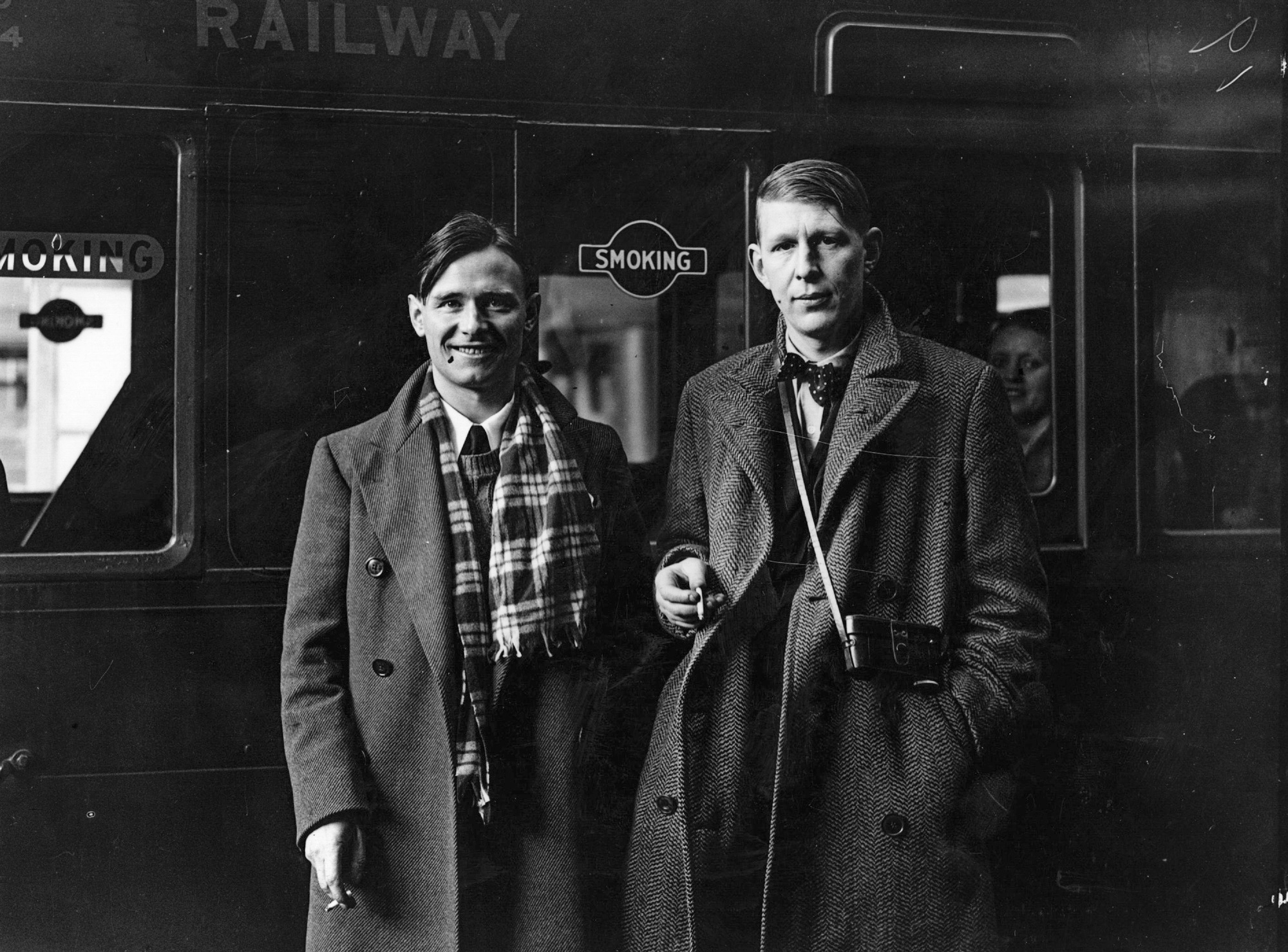

There is a photograph, taken in 1938, of the English poet W. H. Auden with his friend, sometime lover and fellow writer Christopher Isherwood, about to board a train at London’s Victoria station. A sign on the carriage window behind them announces that this is a smoking car, and both Auden and Isherwood are dutifully holding half-smoked cigarettes in their left hands. Isherwood, the shorter of the two, looks boyishly fresh-faced; he is standing straight and smiling. Auden looms next to him, slightly hunched, the collar of his tweed coat pulled up, his craggy face pensive. Just behind Auden’s left shoulder, a young woman looks out from the carriage; she is also smiling.

Auden and Isherwood had been commissioned by their publisher to write a travel-diary and were about to embark on a journey to China, then in the second year of war against Japan. The resultant book, featuring verse by Auden, prose by Isherwood, and a number of graphic war photographs, was published as Journey to a War in 1939.

This photograph is fascinating, as it seems to prefigure a theme which surfaces repeatedly in Auden’s work, perhaps finding its most famous expression in his poem Musée des Beaux Arts, completed just after he returned from China: that of people’s indifference to suffering. It is embedded in the poem’s opening lines above: the word ‘suffering’ which is thrust in front of us, only for the poem to meander away from it in that extraordinarily long fourth line. It is not that Isherwood was unresponsive to the horrors of war; he certainly wasn’t. But it is hard not to be struck by the context of the photograph—the impending expedition into a warzone, the terrible descent into world conflict. It is as though only the grim-faced Auden, like the old masters whose paintings he so admired in the museum of fine arts in Brussels, has a premonition of the ‘dreadful martyrdom’ to come.

The extraordinary realisation on reading Musée des Beaux Arts is that we are shocked not by human tragedy but by human reaction to that tragedy: a meta tragedy. The poem is ekphrastic: the re-creation of a work of art in words; in the poem, Auden describes an early Flemish painting depicting the character of Icarus from Greek mythology. Icarus attempts to escape imprisonment on wings made from feathers and wax but ignores his father’s advice not to fly too close to the sun; his wings melt and he plunges into the sea, where he drowns. In Breughel’s painting, all that is seen of the disaster are two small, pink legs flailing helplessly above the water, while front and centre are dominated by a farmer and a shepherd, each studiously looking the other way.

Auden scorned the attempts of other writers to portray suffering: the ‘versified trash’ produced following the massacre of the Czech village of Lidice in 1942, for example. ‘[W]hat was really bothering the versifiers’, he concluded, ‘was a feeling of guilt at not feeling horrorstruck enough.’ A good war poem, he said, would have ‘told how, when he read the news, the poet...went on thinking about...his lunch.’

Photo copyright Hulton-Deutsch Collection via Getty Images

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025