Publication

Regulatory investigations and enforcement: Key developments

The past six months have seen a number of key changes in the regulatory investigations and enforcement space.

Indonesia | Publication | September 2025

In response to the United Nations’ 21st Conference of the Parties (COP-21) in 2015, Indonesia enacted Law No. 16 of 2016 on the Ratification of the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In its 2022 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) document, Indonesia has targeted the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 31.89% by 2030 through domestic measures or by 43.2% with international support. The government also plans to gradually replace fossil fuels by shifting to renewable energy, with a long-term goal of achieving net zero by 2060.

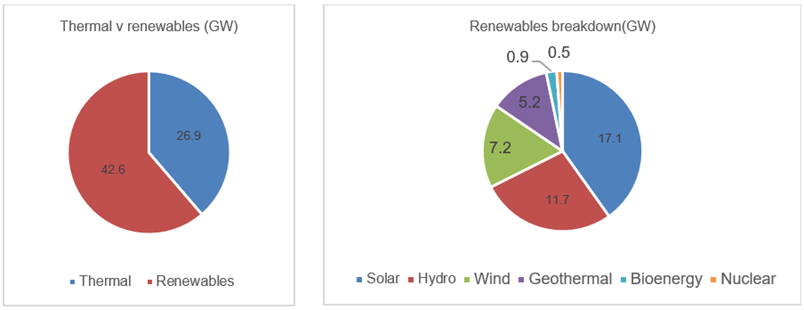

Indonesia’s state-owned electricity utility, PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (Persero) (PLN), issued the new Electricity Supply Business Plan (Rencana Usaha Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik or RUPTL) in May 2025. The RUPTL relates to the period 2025-2034 and sets out plans in relation to the construction of new generation assets with capacity of 69.5 GW, of which 42.6 GW would come from renewable energy sources and an additional 10.3 GW of energy storage (battery energy storage system (BESS) and pumped storage). 73% of new capacity is reserved for independent power producers (IPPs), including a majority of the renewable energy projects.

Of the renewable energy projects, the greatest volume has been reserved for solar (17.1 GW), followed by hydro (11.7 GW), wind (7.2 GW), geothermal (5.2 GW), bioenergy (0.9 GW) and nuclear (0.5 GW). The majority of the renewable energy projects are targeted for development in the 2030 – 2034 period. The RUPTL specifies the expected geographical spread of the renewable projects. For example, the majority of the solar capacity proposed has been allocated to Java, Madura and Bali. The remaining capacity is divided evenly between Sumatra, Kalimantan and Maluku, Papua and East Nusa Tenggara. The geographical spread of proposed capacity tends to reflect solar irradiation potential, rather than suitability of the transmission facilities. In some regions, there is limited transmission infrastructure, while other areas suffer from transmission congestion.

Addressing baseload requirements and the need to balance intermittent renewable energy capacity, PLN targets additional thermal generation capacity of 16.6 GW, for development during the 2025-2029 period, as well as new transmission lines and substations of 47,758 kms and 107,950 MVA respectively during the next ten years.

PLN is keen to support electrification for industrial use, including downstream processing industries. PLN may fast track projects outside of the RUPTL that serve national strategic projects or other strategic industries (subject to ministerial approval).

Presidential Regulation No.112 of 2022 on the Acceleration of Renewable Energy Development for the Supply of Electricity (PR 112/2022) was promulgated in September 2022 and established a roadmap for the retirement of coal-fired power projects (CFPPs) and the expansion of renewable energy sources. PR 112/2022 prohibits the development of new CFPPs unless they meet the conditions set out below:

As such, PR 112/2022 preserves the ability for certain industrial players to utilise captive CFPPs to support industries such as nickel refining, which is a significant user of coal-fired generation.

PR 112/2022 does not address the early retirement of existing CFPPs. As yet, there is no specific schedule for CFPP retirement, in part due to the lack of legal framework to retire IPPs that are under long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) with PLN, as well as funding shortfalls. Nevertheless, the early retirement of the first CFPP, the Cirebon 1 660 MW project, is proposed in 2035, five years ahead of the scheduled end of the PPA term. This was enabled through financial support from the Asian Development Bank.

In light of the above, PLN’s latest RUPTL sends a mixed message. The latest RUPTL contemplates the development of 6.3 GW of new CFPPs, mainly consisting of mine-mouth projects. PLN proposes that these are developed in the 2025 – 2029 period. Of the 6.3 GW, 2.3 GW are already in development. The new CFPPs are excluded from the partial moratorium provided under PR 112/2022 on the basis that they are considered necessary to support the grid and other strategic industries (i.e., they fall within the second condition referred to above). The Indonesian government further justifies the new CFPPs on the basis that mitigation strategies will be employed, including the development of solar and BESS projects in Sumatra and Kalimantan in proximity to the new CFPPs. The CFPPs are also expected to utilise technological solutions to mitigate emissions and increase efficiency, including co-firing with biomass or ammonia and, in the longer term, carbon capture and storage technology.

Indonesia favours an auction process with a tariff ceiling. Projects are procured under differing methods, according to the renewable energy source/technology. These are explained below.

Direct selection – this applies to hydro, solar, wind, biomass, biogas and tidal projects. Under this procurement method, pre-qualified participants are invited to bid against the capacity and technical requirements of the projects being procured by PLN. The pre-qualified participants must have previously registered and fulfilled the requirements to be listed on PLN’s lists of selected providers (daftar penyedia terseleksi – DPT). Tenders are based on a capacity quota and competitive pricing against a ceiling price, which is determined based on the technology, capacity and location factor of the relevant project.

Direct appointment - this applies to:

Under this procurement method, PLN engages directly with the applicable IPP and the tariff is subject to agreement between the parties. In practice, PLN generally references the applicable ceiling prices or the average cost of generation on the relevant local grid (known as the biaya pokok penyediaan pembangkitan - BPP).

The RUPTL indicates that certain hydro projects and floating solar projects might be developed through the public private partnership (PPP) scheme under Presidential Regulation 38 of 2015 on Cooperation between Government and Business Entities in Procurement of Infrastructure.

Since 2017 many projects procured by PLN have involved equity participation by PLN’s subsidiaries, PLN Indonesia Power, PLN Nusantara Power and PLN Nusantara Renewables, including the Java 9 & 10 coal-fired project and the Cirata floating solar project.

These PLN partnership arrangements arise in one of the following two ways:

Mandatory partnership: the tender for the project specifies that a PLN subsidiary will take a minority ownership interest in the project. In practice, this is typically in the range of 15 – 35%.

Cooperation partner: PLN or its subsidiary acts as a “cooperation partner” taking an equity interest in the project company of 51%1.

The market has generally viewed these projects as being less attractive than 100% privately owned IPPs. In part this is due to the drag on the potential return on investment for the non-PLN shareholders as the PLN subsidiary does not contribute equity upfront or its contribution is capped. Generally, the PLN subsidiary’s share of equity is loaned by the remaining shareholders, which is repaid by the PLN subsidiary through its share of dividends from the project company.

Further, the participation of PLN’s subsidiary in the transaction tends to cause delay and increase transactional costs due to the additional structuring required, as discussed below.

Where PLN or its subsidiaries act as a cooperation partner, careful structuring has been necessary to ensure the project’s bankability. Key aspects include:

Decision making: all shareholder decisions are structured so that they fall within the joint control of the PLN subsidiaries and the independent investor. i.e., unanimous consent is required.

Conflicts of interest: directors or commissioners appointed by the PLN shareholder are excluded from decision making on matters where they have a conflict of interest, including enforcement of rights against PLN under the PPA for the project.

World Bank Negative Pledge: the government of Indonesia and PLN are borrowers from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). The terms of their loans include a negative pledge that provides that public assets may not be secured for the benefit of third parties unless IBRD is granted pari passu security. The concern is that the assets of the project company could be construed as public assets and therefore restricted from being secured in favour of project lenders, if the project company is controlled by a PLN subsidiary. This can be managed with careful structuring of the corporate governance of the project company, including joint control, as discussed above.

Claims against PLN: PLN undertakes that it will ensure that its subsidiary shareholder will comply with its obligations under the shareholders’ agreement and articles of association of the project company. This provides the independent investor with a contractual claim against PLN if its subsidiary breaches the joint control provisions.

In March 2025 the government of Indonesia issued Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) Regulation No. 5 of 2025 on Guidelines for Power Purchase Agreements from Power Plants Utilizing Renewable Energy Sources (MEMR 5/2025). This sets out a specific set of guidelines that apply to the PPAs for the offtake of power by PLN from renewable energy projects (solar PV, wind, geothermal, hydro, biomass, biogas, biofuel, tidal and waste-to-energy, with or without BESS). MEMR 5/2025 applies to projects that did not yet have a signed PPA when it was issued, including projects that are currently in the tender process before the submission of proposals.

Largely, MEMR 5/2025 codifies the precedent provisions that have developed in recent years under Indonesian PPAs that have been financed. However, the drafting of the regulation contains ambiguities, leaving some doubt as to how PLN will approach future PPA negotiations. MEMR 5/2025 establishes guidelines and, in theory, PLN and developers are free to contract out of these guidelines. In practice, however, we expect PLN to take a conservative approach, which might limit the extent to which PLN is willing to derogate from the guidelines set out in MEMR 5/2025. For now, it is a matter of wait and see until PLN issues a revised model PPA for use in the procurement process.

Key aspects of MEMR 5/2025 include:

Project structure: build, own, operate (BOO), build, own, operate, transfer (BOOT) and other development and operating schemes are permitted. BOO and BOOT are the structures most likely to be adopted, which is consistent with current market practice.

PPA term: PPAs may have a maximum term of 30 years, with the possibility of an extension of the term by agreement. The extension of the term may apply if the project company has suffered force majeure during the initial term of the PPA or, more widely, if it is in the economic interests of both parties.

Take or pay: MEMR 5/2025 generally refers to PLN’s obligation to purchase electricity. It is, however, not clear what this will mean in practice. We would generally expect intermittent energy sources to be subject to an energy-based tariff (with a guaranteed level of offtake – “contracted energy”) and non-intermittent projects to be subject to capacity payments. MEMR 5/2025 refers to availability factors, which suggests that a capacity payment structure might still be available for appropriate projects (e.g., hydro projects with a reservoir).

Grid failure: Under MEMR 5/2025 it is unclear how much grid related risk is borne by PLN. Ordinarily, we would expect PLN to bear the risk of grid failure (including force majeure affecting the grid), subject to limited cure periods for carrying out repairs. However, under MEMR 5/2025, PLN’s risk appears to be limited to “emergency conditions” and it is relieved of liability where PLN is unable to absorb electricity due to force majeure. It is possible that the language in MEMR 5/2025 is not fully indicative of the intended position and time will tell whether PLN will maintain the position generally accepted prior to the issuance of MEMR 5/2025.

Deemed commissioning and dispatch: MEMR 5/2025 sets out events that give rise to deemed dispatch payments, such as PLN's curtailment for maintenance or an emergency situation. However, the regulation states that PLN will not be obliged to pay for deemed commissioning or deemed dispatch if there is a force majeure event affecting PLN or the grid more broadly (which is contrary to the generally accepted precedent). MEMR 5/2025 allows PLN and developers to agree the events that give rise to deemed dispatch and deemed commissioning in each PPA, which we hope will enable PLN to agree broader deemed commissioning and deemed dispatch events that are consistent with previously financed PPAs.

Performance penalties: Under MEMR 5/2025 project companies may be liable for performance related penalties based on availability factor, contracted energy, performance ratio or other technical criteria specified in the PPA. Whilst the regulation is unclear about which mechanism applies to a particular project, based on prior practice, we expect that the mechanism for applying performance related liquidated damages will vary based on the technology employed and will be adjusted for the renewable energy resource. We would also expect the performance related damages to be capped. One helpful change introduced by MEMR 5/2025 is that penalties for run of river hydro, solar, wind and tidal projects are assessed annually, rather than monthly as per previous practice.

Force majeure: MEMR 5/2025 introduces a more restricted definition of force majeure than prior PPAs. It consists of three exhaustive events, as follows:

In each case, these events may only be considered as a force majeure event if there is a determination from the relevant authority. This differs from precedent and there is a risk that localised events might not be categorised as a force majeure event.

MEMR 5/2025 suggests that PLN and the project company are not permitted to include other events (e.g., strikes and industrial action) unless the MEMR approves that inclusion. It is unclear how the MEMR approval process is intended to operate – e.g., will it be obtained prior to PPA execution or once the event has occurred.

Time will tell whether PLN will continue to use its precedent definition of force majeure, which includes governmental related acts. Unless this is satisfactorily resolved in practice, this could be a key bankability issue, in part because of the relief that will be available to the project company for its performance obligations, but also in terms of the deemed commissioning and deemed dispatch provisions, which are a core bankability feature of previous Indonesian PPAs.

Change in law: MEMR 5/2025’s coverage of change in law is not as express and comprehensive as the position under prior regulations. MEMR 5/2025 allows for tariff adjustments due to changes in tax, environmental obligations, non-tax state revenue and other terms and conditions agreed upon by the parties in the PPA (which, if agreed, could include general changes in law). It remains to be seen whether PLN will continue the prior practice of allowing tariff adjustments for all changes in law. Any tariff adjustment arising from a change in law is subject to the approval of MEMR if the adjusted tariff would exceed the then applicable tariff ceiling published under Presidential Regulation 112/2022 on Renewable Energy. This might be considered to be a setback compared to the previous position where ministerial approval was not required.

Fuel: the project company bears the risk of availability, and the pass through of the cost, of fuel for biomass, biogas, biofuel and steam for geothermal power projects.

Currency: consistent with prior practice, the risk of currency convertibility rests with the project company whereas the risk of exchange rate fluctuation rests with PLN. US dollar denominated components of the tariff will be paid in IDR based on the Jakarta Interbank Spot Dollar Rate (JISDOR) applicable one day before the payment date.

BESS / storage: MEMR 5/2025 treats storage systems as an integral part of the power project. The electricity transaction is based on the total energy recorded at the transaction point, which includes energy generated by the power plant and any stored energy delivered. MEMR 5/2025 also addresses the replacement of storage systems that have reached the end of their lifespan. The project company is required (at its own cost) to replace these with new systems with the same or improved performance.

Performance security: MEMR 5/2025 caps performance guarantees at 10% of the total project cost, which is consistent with current practice. PPAs typically require two performance securities, which secure achievement of the financing date (meeting the requirements for financial close) and the commercial operation date. These performance securities are provided at signing of the PPA. The PPA requires the performance securities to be provided by the project company. In practice they are procured by the sponsors of the project company and are therefore a form of completion support by the sponsors. MEMR 5/2025 does not specify a minimum level of performance security and it remains to be seen whether PLN will consider a lesser amount for larger projects, which would align better with regional precedent.

Liquidated damages: MEMR 5/2025 specifies that delay liquidated damages will be calculated by reference to the cost of the project. This is a welcome change from previous precedent where liquidated damages were calculated by reference to the local BPP rate, which is typically higher than a calculation based on project cost. Again, this better aligns Indonesia with regional precedent.

Environmental attributes: PLN and IPPs may agree between themselves on the allocation of carbon credits or other environmental attributes generated by a project.

Share transfers: The language of MEMR 5/2025 is difficult to interpret – it refers to a transfer of shares to lenders exercising their step-in rights rather than transfers of shares to new equity investors in the IPP. Whilst these are two distinct concepts, it appears that lenders are now permitted to enforce their share security and transfer shares in the project company to a third-party buyer before the commercial operation date, subject to the transferee having comparable qualifications and PLN's prior consent (which is a potential bankability issue).

Refinancing: MEMR 5/2025 requires the PPA to address the issue of refinancing with the aim of optimising the implementation of electricity supply activities. It is not yet clear what this means in practice, in terms of the allocation of any potential refinancing gains.

For several years at the early stages of the Indonesian IPP industry, a government guarantee from the Ministry of Finance was an integral part of every project structure and critical to achieving financial close. During a transition phase, a “letter of comfort” was issued in lieu of a guarantee. In recent years, with the improvement of PLN’s credit rating (which is linked to the Indonesian government credit rating), IPPs have not received a government guarantee and financings have closed without the need for one.

Theoretically, regulated pathways still exist for the provision of government guarantees supporting renewable projects, but we think it is unlikely that a guarantee will be provided unless a particularly large scale and strategic project requires the provision of a guarantee in order to attract appropriate investors.

One of the possible and newest pathways to a government guarantee is via Regulation No. 5 of 2025 on Guidelines for the Granting and Implementation of Government Guarantees and Risk Taking in the Acceleration of Renewable Energy Development in Electricity Generation (MOF 5/2025) issued by the Ministry of Finance in January 2025. MOF 5/2025 permits the government of Indonesia to provide guarantees to renewable power projects and geothermal power projects. The government guarantee will cover the risk of government action/inaction and PLN's action/inaction, including PLN's inability to perform specific PPA obligations.

Despite the seemingly good intentions behind this regulation, it may be of little use to developers of renewable projects. The guarantee applies to 'infrastructure risk', which is defined as any event that might affect a renewable project during the term of the PPA that negatively impacts the IPP’s investment (i.e., equity and debt). The debt may be provided by an institution, a multilateral financial institution, or a financial institution of a government holding diplomatic bilateral relations with Indonesia that directly provides a loan to an Indonesia state-owned company. This drafting is troublesome as it effectively excludes any loan received by an IPP, which is the typical means by which IPPs are financed.

Further clarification and amendment of MOF 5/2025 may be required before it can provide any meaningful opportunity to enhance the financings of renewable projects in Indonesia. In the meantime, IPPs are limited to the existing (but quite restricted) routes to government guarantees and support applicable to PPP projects and legacy projects under the second fast track programme of 20102.

High local content requirements in Indonesia previously presented a challenge to renewable developers, particularly in the solar sector, given limited capacity in the local supply chain. In some projects, this required project developers to collaborate with Indonesian equipment manufacturers to satisfy local content requirements. A further challenge existed where projects sought finance from export credit agencies (ECA) that was linked to procurement from the ECA’s home country.

In July 2024, the government of Indonesia enacted regulations related to local content requirements for new power projects in Indonesia. These regulations shift the authority over local content thresholds for power projects from the Ministry of Industry (MoI) to the MEMR and attempt to address some of the difficulties experienced by power project developers in the past.

Like its predecessor, MEMR Regulation 11 of 2024 on the Utilization of Local Products for Development of Electricity Infrastructure (MEMR 11/2024)3, applies to electricity projects for public use, which excludes captive projects and projects with corporate and industrial (C&I) offtake. Projects subject to MEMR 11/2024 include those that are developed by:

(i) a government body; and

(ii) a state or regional owned company (including PLN and its subsidiaries) or a private company.

In the case of (ii), local content rules apply where the following conditions are met:

MEMR 11/2024 imposes local content requirements on the basis of a total aggregate amount of goods and services. This is a welcome change to the previous requirements which applied on a component-by-component basis. One exception, however, is the requirement to procure specific products domestically based on the Domestic Product Appreciation Book (Buku Apresiasi Produk Dalam Negeri) issued by the Directorate General of Electricity and Directorate of New and Renewable Energy.

The local content requirements set out mandated levels of local content and the applicable goods and services to which it applies. A brief overview of the requirements applicable to renewable generation is as follows:

| Generation type | Aggregate local content requirement for combined goods and services |

| Geothermal |

60 MW or less: 24% More than 60 MW: 29% |

| Hydro |

10 MW or less: 45% 10 – 50 MW: 35% Greater than 50 MW: 23% |

| Wind | 15% |

| Solar | 20% |

| Biomass | 21% |

| Biogas | 25.19% |

| Waste to energy | 16.53% |

MEMR 11/2024 exempts projects from the local content requirements where they are financed from foreign loans and grants provided that they meet the following conditions:

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has signalled plans to ease Indonesia’s local content regulation and certain import restrictions. The potential relaxation comes in response to recent US tariff increases on Indonesian imports. The government is yet to enact relevant regulations and has stated that any regulatory loosening would be carefully evaluated and selectively implemented.

Commencing in 2021, the Indonesian government has introduced several laws and regulations to develop a regulatory framework on carbon trading. These laws and regulations include:

In addition, the Indonesia Stock Exchange has issued several implementing regulations on the trading of carbon units.

Amongst other things, Law 4/2023 establishes and implements a domestic carbon market. Domestic and international carbon units may be traded directly between parties or through the domestic carbon market (or “carbon exchange”), subject to meeting regulatory requirements. The Indonesia Carbon Exchange (IDXCarbon) was officially launched in September 2023 for domestic carbon trading and January 2025 for international carbon trading. To date, the carbon units available for trading relate only to carbon reductions from power projects and carbon offsets from the forestry sector.

PR 98/2021 and MOEF 21/2022 established a "cap and trade" mechanism (i.e., allowance market) and a "cap and tax" mechanism (i.e., offset market). Through these mechanisms the government plans to progressively introduce mandatory emission caps and a carbon tax across certain sectors.

The “cap and trade” mechanism creates a compliance carbon market. Specified business entities are subject to a “cap”, or emission quota allocated for a certain period. Business entities that exceed the cap may purchase carbon units from other business entities that have unused quotas. The “cap and trade” mechanism permits carbon trading through carbon markets and direct trading between parties.

Through the "cap and tax" mechanism, business entities trade carbon units generated from greenhouse gas reduction by certain businesses and/or other climate change mitigation actions. Business entities may purchase carbon units to achieve their emission reduction targets and to fulfil their commitment to carbon-neutral or net-zero goals.

Before carbon units can be transacted through IDXCarbon they must be recorded with the National Registry System for Climate Change Control (Sistem Registrasi Nasional Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim or SRN PPI). SRN PPI is an online data and information management and provision system on actions and resources for climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, and carbon economic value and is managed by the MOEF. In addition, the carbon units must be registered with a domestic carbon exchange administrator, which is a licensed entity responsible for administering and implementing the carbon market.

Carbon units must take one of two forms:

In February 2023, the MEMR launched carbon trading for power projects owned by PLN and IPPs. MEMR 16/2022 authorises MEMR to issue Technical Approval on the GHG Emission Ceiling (Persetujuan Teknis Batas Atas Emisi or “GHG Emission Ceiling”) for each type of power project. This approval determines the maximum emission levels of power plants during specific periods. The GHG Emission Ceiling will be implemented in three phases:

During Phase One, the GHG Emission Ceiling applied to grid connected CFPPs of 25 MW or greater (excluding captive projects). Phases Two and Three have not yet been determined but are expected to expand the list of applicable projects to include off-grid CFPPs, gas-fired power projects and all remaining fossil-fuel generating plants.

Carbon trading in Indonesia is considered a financial transaction or “security” and is subject to the oversight of the Indonesian Financial Services Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan or OJK).

The Electricity Market Authority of Singapore plans to issue import licences for the import into Singapore of up to 6 GW of electricity from renewable sources by 2035. This was increased from the 4GW originally intended, given strong interest from power project sponsors. The EMA has now issued conditional licences (for six separate projects with aggregate import capacity of 3.0GW) and a conditional approval (for an additional project with an import capacity of 0.4GW) in relation to power generation projects that intend to generate renewable electricity in Indonesia and export it as non-intermittent electricity to Singapore.

In 2022 and 2023, the Indonesian and Singapore governments signed three memoranda of understanding (MOUs) that relate to facilitating cross-border trading projects and interconnections between Indonesia and Singapore and investments in the development of renewable energy manufacturing industries, such as solar photovoltaics and battery energy storage systems in Indonesia.

We understand that interaction between Singapore and Indonesian authorities is currently continuing to establish the overall regulatory and commercial framework in accordance with which such projects may proceed.

Publication

The past six months have seen a number of key changes in the regulatory investigations and enforcement space.

Publication

The insurance industry is facing a rapidly changing litigation environment. Emerging risks, regulatory developments, and technological advancements are reshaping how insurers approach underwriting, claims, and risk management. Below is an overview of the most significant trends impacting the sector.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025