On 25 April and July 18, 2025, the Dutch Supreme Court issued new rulings that further clarify the scope and application of the anti-abuse provisions in the Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act 1969 (CITA) and the Dutch Dividend Withholding Tax Act 1965 (DWTA).

These judgments provide new guidance for holding structures — particularly personal holding companies — and offer practical insight into how the anti-abuse rule should be applied in real-world scenarios.

While both rulings reaffirm the importance of genuine economic rationale, they also highlight how timing, intent, and the evolution of a structure influence the assessment of abuse.

Below, we summarise both rulings and highlight the lessons that can be drawn from them.

Background

Central to both cases is the interpretation of the anti-abuse rule, which requires two cumulative conditions to be met:

- the foreign shareholder holds the shares with the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, to avoid the levy of Dutch tax at the level of another person (the Subjective Test); and

- the shares in the Dutch distributing company are held as part of an artificial arrangement or transaction or series of artificial arrangements or transactions (the Objective Test).

Under the anti-abuse rule, tax authorities are required to demonstrate both a tax avoidance motive and the presence of artificial arrangements.1 Once this has been established, the taxpayer may argue that the structure serves legitimate business purposes. The Supreme Court rulings of April and July 2025 build on this framework: they assess whether specific holding structures satisfy these criteria and provide further clarification on the practical application of the anti-abuse rule.

The April Rulings

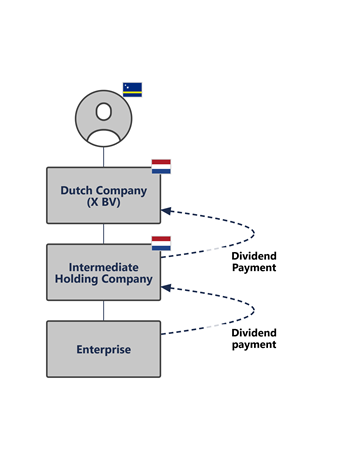

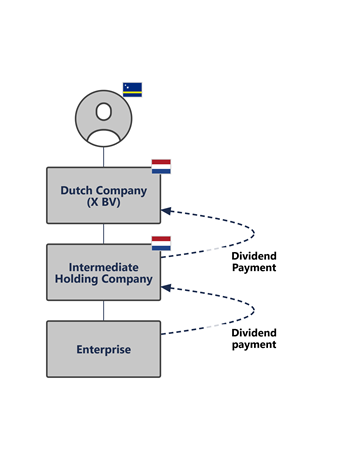

The first cases issued on 25 April 20252 (the April Rulings) involve a Dutch private limited liability company (X BV), acting as a personal holding company for its shareholder residing in Curaçao. The company became Curaçao-resident in 2011 after the emigration of its director. In 2016, X BV received a dividend through a Dutch intermediate holding structure. The Dutch tax authorities sought to tax the dividend under the anti-abuse rule, arguing that X BV’s only purpose was to avoid Dutch income or dividend tax at the level of the non-Dutch shareholder.

The relevant part of the group can be illustrated by the following (simplified) structure:

X BV had no personnel, no office space, and only limited administrative activity (carried out by a trust office). Additionally, X BV was not a top holding company (tophoudster) that, based on its activities in the areas of management, policy-making, or financial matters, performs a significant function in relation to the group’s business operations.

However, the Court of Appeal ruled that the taxpayer successfully demonstrated that there was no tax abuse in the case at hand. The Supreme Court confirmed that ruling.

The following circumstances are of importance for the outcome:

- The structure was a common Dutch family holding structure in 2007 (the date of the original setup);

- The structure was not set up with the intention to obtain a tax benefit since it reflected genuine, non-tax motives, including family succession and business structuring;

- X BV qualified as the ultimate beneficial owner of the dividend, as it retained the proceeds and did not (immediately) distribute these to its shareholder; and

- Although changes to the tax treaty between the Netherlands and Curaçao as of 2016 resulted in a more favourable tax position for dividends received by Curaçao-resident companies, the structure had not been amended in anticipation of these changes.

This ruling provides welcome guidance for individuals, family offices, and cross-border groups that rely on intermediate or personal holding companies. It is a strong indication that such entities can fall outside the scope of the Dutch anti-abuse provisions — even if they lack extensive substance or economic activities.

A lack of substance or economic activities alone is not decisive, provided that the overall structure can be explained by practical factors such as family, commercial or historical considerations. In assessing whether a structure is abusive, all facts and circumstances must be considered in their entirety — including why and when the structure was set up, how it developed over time, and whether it reflects genuine economic or personal reasons rather than a purely tax-driven arrangement.

The July Rulings

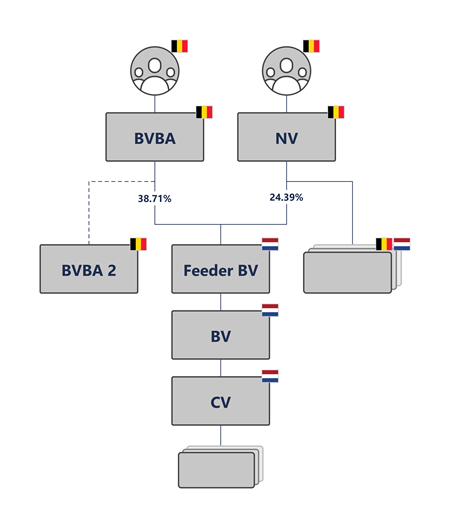

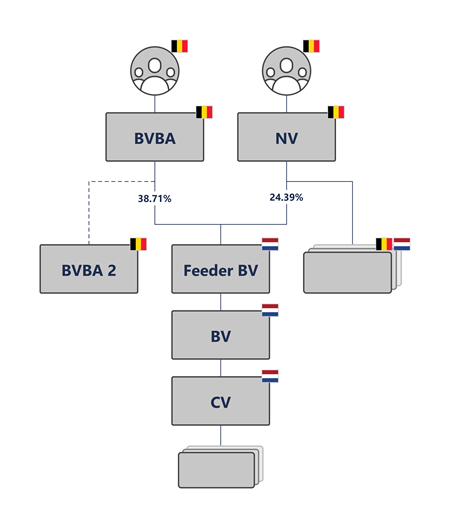

The more recent rulings issued on 18 July 20253 (the July Rulings) concern dividends paid by a Dutch 'feeder company' (Feeder BV) of a private equity fund to two Belgian companies (BVBA and NV) and the application of the Dutch dividend withholding tax exemption. The central issue was whether the anti-abuse rule precluded the application of the exemption. The Amsterdam Court of Appeal had previously ruled that abuse was present in both cases, and the Supreme Court upheld these decisions.

The relevant part of the structure can be illustrated by the following (simplified) structure:

In the first case, the Belgian company BVBA held a 38.71 percent interest in the Dutch feeder company (Feeder BV) and functioned as a Belgian holding for three family members. Originally established to hold shares in another Belgian company operating an energy enterprise (BVBA 2), BVBA invested in the feeder after selling those shares in 2011. At the time of the dividend distribution, BVBA had no other activities and only held the shares in Feeder BV and two vintage cars. Both the District Court and the Court of Appeal found that the structure was artificial and constituted abuse, as BVBA lacked substance and did not justify its existence beyond pooling investments.

Importantly, the Supreme Court clarified that the assessment of whether a structure is abusive is not limited to the time it was set up. Even if a structure was originally established for valid commercial reasons, it can later become abusive if it is maintained despite changes in circumstances that remove its original justification.

In contrast, in the second case, the Belgian NV held a 24.39 percent stake and managed investments for a Belgian family, actively overseeing various participations in the Netherlands and Belgium. Notably, the lower court acknowledged the existence of a material enterprise at the level of NV — partly based on a €500,000 management fee — but concluded that the shareholding in Feeder BV could not be functionally linked to that enterprise. However, the Supreme Court denied the application of the dividend withholding tax exemption, reasoning that the NV's interest in the feeder company was not functionally attributable to its enterprise.

The fact that a company operates a material enterprise does not mean that there is no abuse. The relevant shares must also be attributable to that enterprise's assets. It is therefore important that there is active management and control with regard to those participations.

Implications for businesses

Together, these rulings offer a more nuanced understanding of how the Dutch Supreme Court interprets tax abuse in the context of holding structures — and what businesses should do to remain compliant.

While both rulings apply the same legal framework, they illustrate different angles of the abuse test in practice:

- The April Rulings shows that a structure with limited substance can still be upheld if it is and continues to be rooted in genuine, longstanding non-tax motives (e.g. family succession, business continuity) and has not been altered to benefit from (beneficial) changes in tax law.

- The July Rulings, by contrast, demonstrates that even a structure that was initially valid could become abusive if it no longer serves a commercial purpose and is not adapted to reflect changed circumstances. Additionally, The Supreme Court clarified that the presence of a material enterprise does not preclude abuse, unless the shareholding is functionally linked to that enterprise. The degree of control over dividend distributions and the absence of reinvestment obligations were also relevant factors.

These rulings underscore that the assessment of whether a structure is abusive must consider its entire lifecycle — not just the moment it was established or the dividend is distributed. A structure that begins with legitimate commercial intent may later become abusive if it no longer reflects economic reality and is not adapted to changing circumstances. Conversely, a structure with limited substance may still be upheld if its original rationale remains credible and consistent over time. This dynamic approach can work both in favour of and against taxpayers, depending on how well the structure continues to align with genuine business purposes.