COP30 decisions

At the COP summits, national delegations negotiate under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which includes the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and 2015 Paris Agreement. We also tend to see sideline announcements on a range of climate-related initiatives.

In this section, we cover the outcomes of the formal UNFCCC COP30 negotiations.

Global Mutirao Decision

COP Presidencies often incorporate an overarching ‘cover decision’ into the negotiations to deal with political issues which are not properly addressed elsewhere in the COP decisions. After four topics did not make it onto the COP30 agenda despite strong lobbying efforts, some parties suspected these would be wrapped up in a cover decision. These topics were unilateral trade mechanisms (UTMs), climate finance, ambition to maintain average temperature warming below 1.5 degrees and emissions data transparency.

Early in the second week, these expectations were confirmed when the first version of a Global Mutirao Decision was published. This underwent intense negotiations which were criticised for lacking clear leadership from the Presidency, before being adopted at the COP30 closing plenary.

The final Global Mutirao Decision included the following items (discussed in more detail below):

- An updated adaptation finance target to be achieved by 2035.

- An affirmation of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) whilst calling on parties to urgently scale up finance for developing countries to achieve the NCQG by 2035.

- An acknowledgement of collective progress on the Paris Agreement temperature warming targets, whilst “noting that this is not sufficient to achieve the temperature goal”.

- An affirmation that climate measures should not “constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade”.

TAFF

At COP28 in Dubai, UAE, parties had agreed on the need to transition away from fossil fuels (TAFF). At the leaders’ summit ahead of COP30, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva stated:

“Despite our difficulties and contradictions, we need roadmaps to justly and strategically reverse deforestation, overcome dependence on fossil fuels and mobilise the necessary resources to achieve these goals.”

This was the first public call for a TAFF roadmap, although the COP Presidency had apparently been consulting on this option prior to COP. Momentum for a TAFF roadmap built throughout COP30 and ultimately, more than 80 countries supported it, including the countries in the Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS).

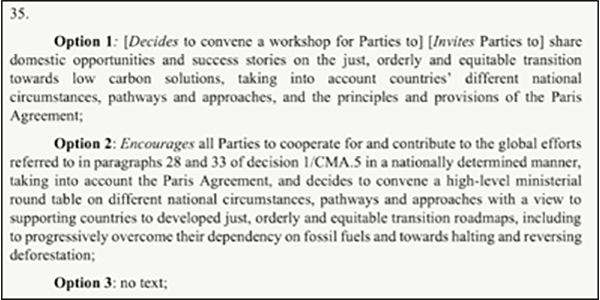

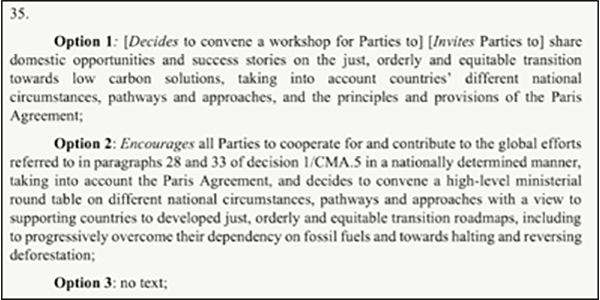

At one stage in the second week, the draft Global Mutirao Decision had the following three options for inclusion of a TAFF roadmap (courtesy of Carbon Brief):

However, later versions had no reference to a TAFF roadmap and it was relayed amongst the negotiators that a TAFF roadmap was a redline for some states, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Whilst there was no TAFF roadmap in the final Global Mutirao Decision, Colombia and Netherlands have agreed to co-host the first annual TAFF summit in April 2026.

Furthermore, Australia’s Climate Minster Chris Bowen – who will likely be the COP31 President – has already said that Australia will “continue to argue” for a transition away from fossil fuels.

Adaptation

Heading into COP30, adaptation was a major focus for two reasons:

- At COP26, parties agreed to double adaptation finance to $40 billion by 2025 – as such, parties this year needed to land on an updated target for the coming years.

- Parties had yet to agree “indicators” for measuring progress on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) under Article 7 of the Paris Agreement, which requires “enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change”.

In relation to adaptation finance, developing countries had hoped to see a tripling of the existing target to $120 billion per year by 2030. This was proposed by the Least Developed Countries bloc and was supported by the African Group and AOSIS.

In the end, this timeframe was slightly delayed. The Global Mutirao Decision:

calls for efforts to at least triple adaptation finance by 2035 … and urges developed country Parties to increase the trajectory of their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing country Parties

In parallel to the adaptation finance discussions, parties negotiated the GGA indicators. Some negotiating blocs were divided on the list of potential indicators. Amongst other comments, parties called the indicators “intrusive” and observers recognised that about half of them would only be possible if developing countries were provided with sufficient adaptation finance.

Towards the end of the second week, the initial list of 100 indicators had been narrowed to 59. To demonstrate the nature of these indicators, the final list includes the following:

Level of water stress, including as an outcome of adaptation actions where applicable, accounting for relevant climate hazard intensity and/or frequency

Proportion of the population using safe and affordable potable water services that are climate-resilient, including as an outcome of adaptation actions where applicable

Level of incidence of climate-sensitive infectious diseases, including as an outcome of adaptation actions where applicable

Proportion of cultural heritage protected from climate impacts through digitization measures for preservation and recovery and by storing movable heritage in climate-resilient facilities

Whilst there were some complaints in relation to the pace and conduct of the negotiations, it seems the overall impression was that it was satisfactory that an agreed list would enable the implementation of adaptation efforts.

1.5 Ambition

Prior to COP30 starting, the synthesis report prepared by the UNFCCC Secretariat on Parties’ updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) found that “Parties are bending their combined emission curve further downward, but still not quickly enough”. This was against the wider backdrop of 2024 being the first year the average global temperature exceeded 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

As such, there was a desire to incorporate a call for increased ambition into the COP30 decisions. This was also reflected in the Global Mutirao Decision which call for:

“…limiting global warming to 1.5 °C with no or limited overshoot requires deep, rapid and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions…”

[and]

accelerating implementation, solidarity and international cooperation, to launch the Global Implementation Accelerator, as a cooperative, facilitative and voluntary initiative … to accelerate implementation across all actors to keep 1.5 °C within reach and supporting countries in implementing their [NDCs] and national adaptation plans..”

Deforestation

At COP26, over 130 countries had pledged to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. Going into COP30, Brazil intended for deforestation to be a headline issue.

Not only was COP30 being hosted in the Amazon, Brazil was championing the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) (discussed below). In his speech at the leaders’ summit, President Lula called for a roadmap on deforestation. As with the TAFF roadmap, this gained momentum during COP (with up to 92 countries backing the proposal) but it did not make it into the final Global Mutirao Decision.

Climate Finance

Beyond the updated adaptation finance target, there was little progress in relation to climate finance besides re-affirming the COP29 NCQG and calling for an accelerated scale up of finance. The Global Mutirao Decision stated that parties:

“…[reaffirm] the call on all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing country Parties for climate action from all public and private sources to at least USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035, takes note of the “Baku to Belem Roadmap to 1.3T…”

[and]

“…[decide] to urgently advance actions to enable the scaling up of financing for developing country Parties for climate action from all public and private sources to at least USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 and emphasizes the urgent need to remain on a pathway towards the goal of mobilizing at least USD 300 billion for developing country Parties per year by 2035 for climate action, with developed country Parties taking the lead…”

Belem Action Mechanism

Prior to the summit, civil society groups had called for a mechanism to provide support for a just transition in countries around the world, with specific support for workers, indigenous communities and other marginalised groups.

During COP30 negotiations, the scope of the Belem Action Mechanism (BAM) (as this mechanism came to be known) varied, and it was unclear if this was intended to be a plan, a knowledge sharing hub, a vehicle for more substantive support, or something else.

In the end, the final COP30 decision provides that the purpose of the “mechanism” is to:

“…enhance international cooperation, technical assistance, capacity-building and knowledge sharing, and enable equitable, inclusive just transitions, noting that the mechanism is to be implemented in a manner that builds on and complements relevant workstreams under the [UNFCCC] and the Paris Agreement.”

The BAM has been highlighted as a key success of COP30 owing to the focus on protecting, amongst other things, human rights, workers’ rights, and the right to a healthy environment.

Unilateral Trade Mechanisms

As discussed above, UTMs was one of the topics which was put to a special Presidency consultation to enable the agenda to be agreed at the start of COP30.

At a high level, UTMs are measures which some jurisdictions have introduced to impose a cost on imports to reflect domestic carbon pricing (to ensure more emissions-intensive imports do not undercut domestic production). The problem is that this will impose substantial liabilities on high-emitting industries in developing countries, which are generally already facing the most severe effects of the climate crisis.

UTMs came to the fore at this year’s COP because the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will come into effect next year. This will likely be the most significant UTM for lots of countries owing to the size of the EU market. Accordingly, many parties were hoping to use COP30 as a vehicle to obtain amendments to how CBAM will be implemented.

Ultimately, this did not happen. Instead, the Global Mutirao Decision recognises that:

“…measures taken to combat climate change, including unilateral ones, should not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade..”

Moreover, the parties agreed in the text that a high-level dialogue will be held on trade at the June meetings of the Subsidiaries Bodies in 2027 and 2028.

Article 6 Carbon Trading

Article 6 is the carbon trading mechanism of the Paris Agreement and is intended to provide parties with a means to cooperate to achieve more ambitious NDC targets.

At COP29, parties finalised the Article 6 Rulebook, meaning that there is nothing holding back implementation of both Article 6.2 (bilateral co-operative approaches) and Article 6.4 (a UN-operated carbon market). Parties also agreed not to re-negotiate these rules until COP33 in 2028.

However, several debates arose during COP30 in relation to the implementation of Article 6.4. These included concerns with how the Subsidiary Body was dealing with the risk of non-permanence (ie stored carbon being re-emitted to the atmosphere). Its approach meant that it might be unfeasible for most land-based activities, like reforestation, to generate credits under Article 6.4. Additionally, there remains an ongoing and heated discussion as to whether entities should be able to generate credits under Article 6.4 for avoidance activities.

Nonetheless, attempts to re-open the COP29 decisions were quashed. Instead, the decisions were technical in nature. The most noteworthy outcome is that the deadline for the transition of projects from the Clean Development Mechanism to Article 6.4 was extended by 6 months (to June 2026).

COP31 and COP32 Hosts

After a drawn-out process to determine who would host COP31, it was confirmed that the summit will be held in Türkiye with Australia holding the COP Presidency (meaning it can manage the negotiations, for example appoint co-facilitators and determine whether to issue a cover decision). A pre-COP event will be held in the Pacific.

It was also announced that COP32 will be held in Ethiopia, after it fought off a rival bid from Nigeria. This means that COP32 will be the first COP to be held in a least developed country (as classified by the UN).

Sideline announcements

As always, COP30 saw a host of sideline announcements, including new climate-related initiatives. We have captured some of these below, including the TFFF and announcements relating to, amongst other sectors, energy, nature, finance, carbon markets and aviation.

TFFF

In the lead up to COP30, Brazil was championing the TFFF as an initiative to incentivise countries to protect rainforests. The TFFF would work on the basis that countries would be paid a per hectare annual fee for rainforest which is still standing.

Brazil hoped to see $25 billion in commitment from national governments, which it would use to leverage an additional $100 billion from private markets. Unfortunately, this amount was not reached at COP with the total commitments closer to $6.7 billion (including commitments from Norway, France and Indonesia).

The COP30 President has pledged to continue working on the TFFF to reach $10 billion in public commitments before it hands the presidency to Australia in late 2026.

Energy

The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2025 (WEO) was released during COP30. The WEO provides global energy analysis data and trends. It highlighted the divergence between stated policy ambitions and real-world energy trends. Under the “Current Policies Scenario”, global energy demand will rise by 15 per cent by 2035, with oil demand reaching 113 million barrels per day by 2050, signalling continued reliance on hydrocarbons.

Nature

Nine Amazonian states and NatureFinance launched a pilot biodiversity credit market. This ten-year model seeks to alleviate the burden associated with managing protected areas. The Amazon generates about $317 billion in ecosystem services annually, however the cost of managing protected areas currently cannot be utilised to pay for protection services.

34 governments launched the Forest Finance Roadmap. This identifies solutions to close the annual $66.8 billion forest finance gap and introduces the Scaling JREDD+ Coalition, which aims to raise $3.6 billion annually by 2030 for measurable reductions in deforestation.

Finance

COP30 saw the publication of the “Report on the Baku to Belém Roadmap to US$1.3 Trillion” (Roadmap). One of the actions in the Roadmap is to mobilise large-scale private capital for climate investments in developing countries, by addressing costs that currently limit investment. Proposed measures include expanding the volumes of first-loss equity deployed with capped returns or long-term patient return requirements in investment vehicles and deploying guarantees to address credit, political and performance risks and support private investment.

COP30 also built upon efforts to strengthen transparency in climate finance delivery, by announcing the launch of the Global Climate Finance Accountability Framework which aims to further improve transparency, credibility, and trust in climate finance delivery.

Waste

In the waste sector, the No Organic Waste Plan was announced, which aims to reduce methane emissions from organic waste by 30 per cent by 2030, supported by a US$30 million commitment from the Global Methane Hub. The initiative emphasises food waste recovery, circular-economy integration and the formal inclusion of waste workers.

Carbon Markets

In the days prior to COP30, the Coalition to Grow Carbon Markets released its Shared Principles for the use of high-integrity carbon credits. The principles, which are backed by the governments of the UK, France, Kenya and other countries, mirror similar initiatives with a focus on entities both mitigating and offsetting, ensuring credits are generated under rigorous standards, and checking that any offset claims are accurate and substantiated.

During COP30, at least 17 governments adopted the “Declaration on the Open Coalition on Compliance Carbon Markets”, which is focused on knowledge sharing, long-term interoperability, and implementing ambition, effectiveness and fairness in regulated carbon markets. Adopting governments include the EU, UK, Canada, Rwanda and Singapore.

Aviation

In this sector, the key initiative to emerge from COP30 was the “Belém 4x Pledge”, spearheaded by Italy, Japan, India and Brazil and supported by 23 other countries, to quadruple sustainable fuel production and use by 2035. The pledge focused on the need to take comprehensive domestic action to support sustainable fuel development and strengthen international collaboration.