Publication

Supreme Court of Canada rejects narrow interpretation of disclosure standard for “material changes”

The Supreme Court of Canada has released its long-awaited decision on Lundin Mining Corp. v Markowich, dismissing the issuer’s appeal

Canada | Publication | July 22, 2025

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) recently issued a decision rehearing Application No. 16/319,040 (DeepMind Technologies Ltd.; the Application) and maintained that all claims remain rejected under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and § 103. The PTAB denied the arguments presented in the request for rehearing, reaffirmed its new ground of § 101 rejection that was raised during the initial decision on appeal, and did not alter its affirmance of the examiner’s obviousness rejections.

This decision helps illustrate the Board’s approach to evaluating technical improvements in artificial intelligence / machine learning inventions, especially in view of the test for assessing patent subject matter eligibility.

This decision is particularly relevant to technologies involving artificial intelligence and machine learning, especially those focused on continual learning, transfer learning, and multi-task learning.

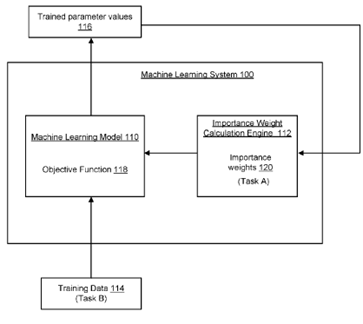

The Application, originally filed January 18, 2019, is directed to a “system [implemented in software] that trains a single machine-learning model on multiple tasks without forgetting previous tasks” (specification, at para. 6).

At its core is a three-step training routine:

FIG. 1 of the Application is reproduced below:

The claims were amended during prosecution to more specifically recite the steps of the training method. For example, the amended independent claim 1 (September 9, 2022 amendment) includes *emphasis added:

“assigning, using the approximation, a value to each of the plurality of parameters, the value being the respective measure of the importance … and approximating a probability that the first value … is a correct value…”

The appellant requested a rehearing, arguing there were specific technical improvements in the field of machine learning that integrate the alleged abstract idea into a practical application, arguing (emphasis from rehearing decision):

“the claimed invention provides specific technical improvements in the field of machine learning by enabling a single model to be sequentially trained on multiple tasks while maintaining acceptable performance on each task. This is achieved without the need to store or maintain separate models for each task, thereby significantly reducing system complexity and storage requirements. Instead of requiring multiple sets of parameters – one for each task – the system retains a single set of parameters, which is adjusted during training on a new task using an objective function that incorporates a penalty term reflecting the importance of parameters to previously learned tasks. This training strategy allows the model to preserve performance on earlier tasks even as it learns new ones, directly addressing the technical problem of “catastrophic forgetting” in continual learning systems.”

The rehearing request principally challenged (i) the Board’s interpretation of “parameter,” (ii) the reliance on the Mehanna reference for a claimed feature, and (iii) the Alice/Mayo eligibility analysis. The panel (Bui, Khan, Curcuri) addressed each argument and did not find any basis to modify its prior decision.

The Board stated the applicant “failed to identify any issue we misapprehended or overlooked.” The Board reiterated that Gordon – not Mehanna – teaches the probabilistic “importance” element because Gordon describes computing a posterior distribution p(w|d,h) over parameters (Decision on Reh’g, p. 5, quoting original decision at p. 15). After this determination, the Board found that arguments regarding Mehanna were no longer relevant to the obviousness analysis. Judge Horvath’s prior concurrence, which distinguished between “feature” and “parameter,” did not alter the outcome.

In the USPTO’s 2019 Revised Guidance, the analysis is set forth in a number of steps:

The Board’s framework tracked the steps under the USPTO’s 2019 Revised Guidance, and Step 2A was considered in more detail in the rehearing.

Step 2A – Prong One (Judicial Exception)

The Board again characterized the claims as “a mathematical concept/calculation to train a machine-learning model” and determined this constitutes an abstract idea (Decision on Reh’g, p. 6).

Step 2A – Prong Two (Integration into a Practical Application)

The request for rehearing argued the methodology “reduces storage requirements” and “addresses catastrophic forgetting.”

However, the panel found no “technological improvement” because the specification “contains no evidence… of a specific means or method that solves a problem in an existing technological process” (id., p. 7).

In the original decision on appeal, the Board found that generic computing elements – “one or more computers” and “one or more storage devices” – do not add significantly more to the abstract idea, and the Board concluded that the abstract idea is not integrated into a practical application.

In the re-hearing, the panel cited prior Federal Circuit decisions in concluding requirements that the machine learning model be “iteratively trained” or dynamically adjusted in the machine learning training are incident to the very nature of machine learning and, as such, do not represent a technological improvement, and that an abstract idea does not become nonabstract by limiting the invention to a particular field of use or technological environment.

Because the § 101 rejection was entered as a new ground in the original decision, the request for rehearing was required to “state with particularity” any points believed to have been misapprehended or overlooked under 37 C.F.R. § 41.52(b)(2). The Board determined that appellant’s request did not identify specific oversight, but instead reiterated arguments previously considered.

This decision may be relevant to innovations relating to systems that aim to train a model across multiple tasks—such as in robotics, autonomous vehicles, natural language processing, and recommendation engines. The decision highlights the challenges in patenting innovations that address issues such as catastrophic forgetting, where a model loses performance on previously learned tasks when trained on new ones.

Despite this application clearly describing a technical problem and corresponding technical solution, the Board downplayed the invention’s technicality and made a simplified analogy in relation to conventional machine learning training.

Developers of AI frameworks, edge computing solutions, and hardware accelerators for machine learning should be aware that improvements limited to algorithmic steps or generic computing environments may not meet the threshold for patent eligibility.

Instead, patent applications in these areas should emphasize specific, technical solutions that go beyond abstract mathematical concepts and demonstrate tangible improvements to computer functionality or system architecture, and during drafting, additional efforts should be taken to anchor the technical improvement in the specification, and include more technical and potentially narrower fallback positions if there is difficult examination.

Publication

The Supreme Court of Canada has released its long-awaited decision on Lundin Mining Corp. v Markowich, dismissing the issuer’s appeal

Publication

Bill C-15, An Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in Parliament on November 4, 2025, has been introduced in the House of Commons and has completed its second reading.

Publication

In November 2025, the Ontario Court of Appeal released a decision quashing a summons issued by an investigator appointed by the Ontario Securities Commission, holding that the summons was unconstitutionally overbroad.

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest legal news, information and events . . .

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025