The historian

Three tales of medieval lockdown | Issue 18 | 2020

—The

historian Jeffrey Anderson on Boccaccio’s celebration of life—

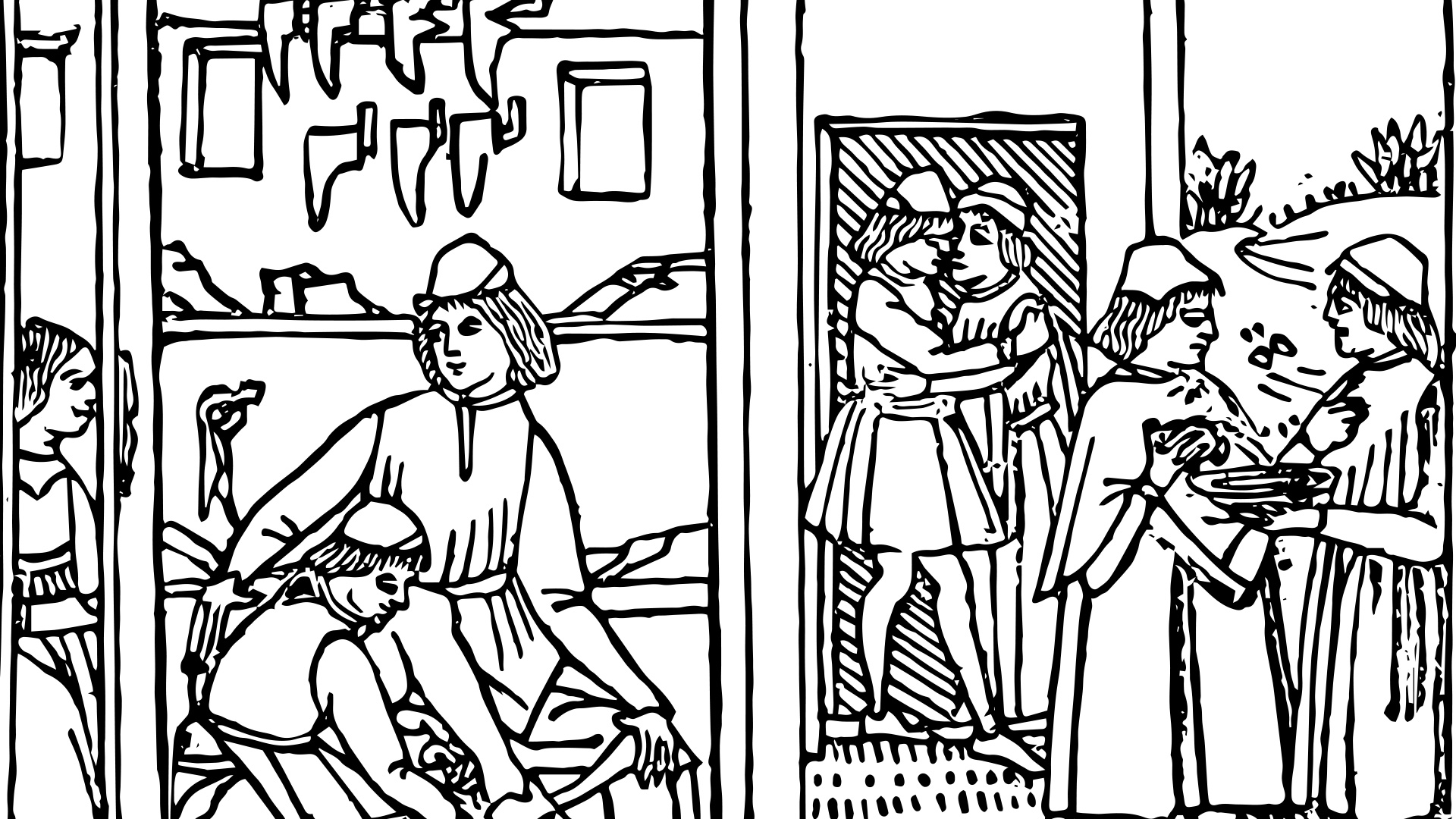

A baker enjoys a glass of wine outside his shop on a warm summer day; two elderly men are caught in the rain and laugh at each other’s bedraggled appearance; a shout startles a flock of cranes at dawn and they fly away: scenes as sharply drawn as the marginal decorations in medieval manuscripts bring fourteenth-century Europe to life in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron.

What gives added poignancy is that Boccaccio wrote the Decameron shortly after the Black Death ravaged Europe from 1347 to 1350, and it consists of a hundred stories ostensibly told over ten days by a group of people who fled Florence to escape the plague and shield themselves in the countryside.

Although Boccaccio was demonstrating his skill as a writer across different genres, more fundamentally his descriptions of ordinary men and women are a celebration of humanity, of people in their infinite variety at a time when more than a third of the population had fallen victim to the plague. Even in the stories that are stylised supernatural fantasies or romances, characters continually shine through as real people—and in some cases they actually are real people, like the artists Giotto and Buffalmacco—with their authentic hopes, fears, desires, vanities and weaknesses.

The Decameron itself gives one of the most horrifying descriptions of the plague, and although Boccaccio drew on earlier sources and may partially have meant this as a rhetorical exercise, he vividly sets out the consequences of the Black Death. His account of people dying unnoticed in their houses, unburied bodies piling up in the streets and trenches dug for mass graves is awful enough, but the social consequences are worse: families locking their doors against relatives for fear of infection, parents abandoning their children, and people veering between rigid observance of quarantine to the exclusion of all social contact and unbridled hedonism as they cavort in taverns careless of the disease they are spreading.

In the face of this catastrophe, Boccaccio conjures a dream of consolation: a group of ten lively young people from Florence decide to shelter in the countryside to escape the disease. They will leave all their cares behind them and amuse themselves by dancing, singing and telling stories. This framing narrative lovingly describes the villas where the group reside (in sufficient detail that certain villas in the hills around Florence still claim to be those mentioned in the Decameron), and the gardens and landscapes where they gather to tell their stories. This invocation of the locus amoenus (‘pleasant place’) is a standard medieval device to denote felicity, and it forms as sharp a juxtaposition with the bustling urban life described in the stories as with the horror of the plague. Crucially, it allows Boccaccio to give us both the idealised leisure of a refined company in a perfect countryside and the gimlet-eyed commerce of the city and joyful physical passions of its citizens, each a vision of the life that the plague had destroyed.

It is the urban, mercantile background to the stories that makes the Decameron notable. The cities of northern and central Italy, particularly Florence, were unusual in being self-ruled entities with an active political life at a time when most other parts of Europe were organised into kingdoms with a rigidly hierarchical society. Although kingdoms like England or France also had a strong merchant class, the dominance of kings, nobles and aristocratic privilege gave their societies a different texture; the vibrant civic context described in the Italian cities feels closer to our own, a context in which a person with guile and daring could make whatever they wanted of themselves, regardless of their birth or family.

Boccaccio himself, born around 1313, was from a merchant family in Florence, and in his travels he met everyone from beggars to kings, the characters who would fill the Decameron. Although he developed a taste for literature that would draw him away from commerce (reputedly after a pilgrimage to the tomb of the poet Virgil in Naples), what makes so many of his stories pulse with vitality is the mentality that underlies them, the mentality of an urban citizenry who dealt with the transactions of the real world, not the rarefied ideal of a chivalric romance.

Although Boccaccio drew on a variety of influences, including history, fables and his business experiences, as well as using historical and popular local figures as characters, the underlying basis of most of the stories is love, sex and relationships. Here, wit and trickery come to the fore, especially when both women and men use their wit to facilitate, excuse or escape from amorous encounters.

In the Decameron, when women are caught with their lovers by their husbands (as happens frequently), they find wildly inventive excuses to justify themselves, and Boccaccio never judges them. Peronella hides her lover in a barrel and explains that she was selling it to him, then condemns her husband for being lazy and a bad businessman; Monna Tessa convinces her husband that a late-night visitor is a demon; and, most strikingly, Madonna Filippa is brought before a court where she argues passionately— and successfully—against the double standard applied to men and women, and the law is changed.

Boccaccio’s eye for detail encompasses both the earthiness of the red light district of Naples—where the character Andreuccio da Perugia finds himself in a house of ill repute and is robbed, dropped into a cesspit and abused by the district’s residents for disturbing their sleep—and technical details, like an accurate account of the dogana in Palermo, the first recorded description of a bonded warehouse, and the procedure by which merchants registered their goods to have them stored safely and taxed.

This vast range of settings and characters led the Decameron to be called the ‘Human Comedy’ in contrast to Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’, and there can be no more fitting epithet for Boccaccio’s achievement. Imitation is another tribute, and the Decameron has frequently been copied and adapted, not least by Geoffrey Chaucer, who refashioned several of its stories and was inspired to create his own rich tapestry of human life in The Canterbury Tales.

These adaptations continue. In February 2020 came the report that an English cast and crew, who had gone to northern Italy to film a new version of the Decameron, found themselves in the midst of a contemporary plague. In an interview, the director Nicholas Hulbert described the oddity of filming scenes from the Decameron as reports of quarantines began to circulate, and considerations such as laying in provisions and potentially being locked down and unable to return home began to impose upon them, even as they filmed scenes inspired by the effects of the Black Death.

Hulbert’s conclusion, just as Boccaccio’s, was that in these times people, and the relationships between them, become the most important thing. That is what Boccaccio celebrates so outrageously, so extremely, layering characters and situations into a grandiose confection that is almost too rich, and for just this reason: in such circumstances we need something this seethingly, uniquely human at a time when people have more need than ever to consider—and value—what it means to be alive.

Jeffrey Anderson’s The Angevin Dynasties of Europe 900—1500: Lords of the Greatest Parts of the World (Marlborough: Robert Hale) was published in 2019.

© Norton Rose Fulbright LLP 2025